In this block, we will consider two regions of the body, the abdomen and pelvis, and the anatomy of the internal organs found there. Although often considered separately, the abdomen and pelvis form the largest effectively continuous visceral cavity of the body (abdominopelvic cavity). They act together to provide multiple vital functions including: support and protection of the digestive and urinary tracts and internal reproductive organs and their associated neurovascular supplies; transmission of the neurovascular supply to and from the thorax and the lower limb; provision of support and attachment to the external genitalia and access to and from the internal reproductive and urinary organs; provision of accessory muscles of physiological actions such as respiration, defecation, and micturition; support for the spinal column in weight bearing and movement.

Osteology

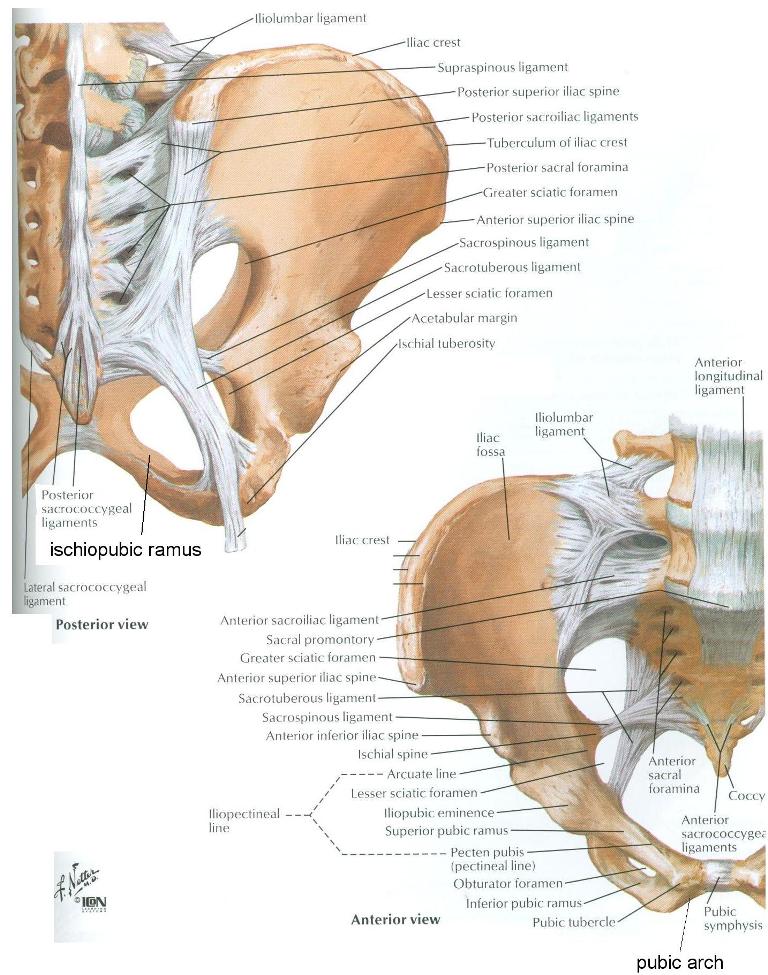

Refer to an articulated bony pelvis and a skeleton. The pelvis (L. pelvis, basin) is formed by two hip bones (coxal bones, ossa coxae) joined posteriorly by the sacrum (Figure 5.2). Each hip bone is formed by three fused bones: pubis, ischium, and the ilium. These three bones are fused at the acetabulum. The coccyx is attached to the sacrum. As you study isolated bones such as the hip bone, compare its features with the articulated bony pelvis and the skeleton.

- On the hip bone (Figure 5.2), identify the:

- Pubic symphysis - midline fusion between the bodies of the right and left pubic bones

- Pubic crest - superior margin of the body of the pubic bone directly lateral to the pubic symphysis. The pubic crest lies within the coronal plane.

- Pubic tubercle - prominence located at the lateral end of the pubic crest

- Superior pubic ramus - stout process extending posterolaterally from the pubic tubercle to the iliopubic eminence (see below). The superior pubic ramus forms the superior boundary of the obturator foramen.

- Iliopubic eminence - prominence at a point of fusion between the ilium and the superior pubic ramus; medial to the AIIS is a shallow groove, over which the psoas major and the iliacus muscles pass on their way to the lower extremity; this groove is bounded medially by the iliopubic eminence.

- Ischiopubic ramus - formed by the ischial ramus, a process that extends superomedially from the body of the ischium, and the inferior pubic ramus, a process extending inferolaterally from the body of the pubic bone. These two rami meet roughly halfway to form a structure collectively called the ischiopubic ramus. The ischiopubic ramus forms the inferior boundary of the obturator foramen.

- Pubic arch - bony arch formed by the right and left ischiopubic rami, right and left bodies of the pubic bones, and the inferior end of the pubic symphysis. Note that the subpubic angle (angle of the pubic arch) is wider in females than in males.

- Ischial tuberosity - prominence at the lateral end of the ischiopubic ramus. The ischial tuberosity is the bony structure that bears one's weight when one sits.

- Ischial spine - pointed process extending posteriorly from the body of the ischium.

- On the sacrum, identify the:

- Sacral promontory - most anteriorly projecting part of the S1 vertebra.

- Anterior sacral foramina - openings permitting the exit of the ventral rami of sacral spinal nerves.

- Identify the coccyx at the caudal end of the sacrum.

- Examine the ischium. Note that the ischial spine divides the posterior margin of the body of the ischium into two large notches - the greater sciatic notch (located superior to the ischial spine) and the lesser sciatic notch (inferior to the ischial spine).

- Using an atlas illustration, study the joint between the sacrum and ilium. The sacroiliac articulation is a synovial joint between the auricular surfaces of the sacrum and the ilium. The sacroiliac articulation is strengthened by an anterior sacroiliac ligament and a posterior sacroiliac ligament (Figure 5.2). The articulation between the ilium and the L5 vertebra is strengthened by the iliolumbar ligament. Do not attempt to find these ligaments on the skeleton or cadaver.

- The hip bone and sacrum are connected by strong ligaments (Figure 5.2). On a model with pelvic ligaments, identify the sacrotuberous ligament, a ligament extending from the inferolateral angle of the sacrum ("sacro-") to the ischial tuberosity ("-tuberous").

- Identify the sacrospinous ligament, a ligament extending from the inferolateral angle of the sacrum ("sacro-") to the ischial spine ("-spinous").

- Note that the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments convert

the greater and lesser sciatic notches into greater and

lesser sciatic foramina, respectively. The greater sciatic foramen is located superior to the sacrospinous ligament. The lesser sciatic foramen is located inferior to the sacrospinous ligament, between it and the sacrotuberous ligament.

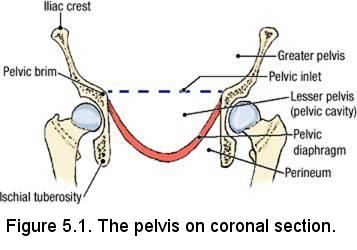

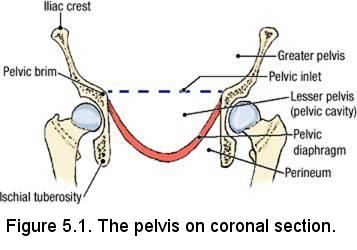

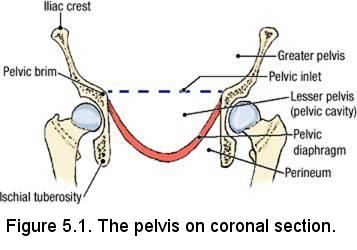

- Identify the pelvic inlet (superior pelvic aperture), a large communication between the greater pelvis (also called the false pelvis or pelvis major) and the lesser pelvis (also called the true pelvis, pelvis minor, or the "obstetric pelvis") (Figure 5.1). The greater pelvis is situated superior to the pelvic inlet and is bounded bilaterally by the right and left alae of the ilium, the wing-like upward projections of the right and left ilia. The concave anterior surface of the ala of each ilium is called the iliac fossa. The cavity of the greater pelvis is considered to be part of the abdominal cavity.

- The bony ridge forming the border around the pelvic inlet is

called the pelvic brim (Figure 5.2, lower right panel). From anterior to posterior, identify the structures that form the pelvic brim:

- Superior end of the pubic symphysis

- Posterior border of the pubic crest

- Pecten pubis (pectineal line) - a sharp line passing along the back edge of the superior pubic ramus. NOTE: The pectineal ligament (of Cooper) is an extension of the lacunar ligament (the lacunar ligament is part of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle that is reflected backward and laterally to attach to the pectineal line; recall that it is also rigid medial boundary of the femoral ring) along the pectineal line of the superior pubic ramus. Cooper's ligament is used in surgical procedures to support pelvic visceral structures that have prolapsed (e.g. the most successful type of pelvic organ prolapse surgery is retropubic suspension. This procedure involves the attachment of the prolapsed structure to Cooper's ligament). You will hear a lot about this in the OB/GYN clerkship.

- Arcuate line of the ilium - continuation of the pectineal line between the ilium and the ischium toward the sacrum.

- Anterior border of the ala (wing) of the sacrum

- Sacral promontory

- The lesser pelvis is located inferior to the pelvic inlet and extends inferiorly to the urogenital and pelvic diaphragms, which close the pelvic outlet (described later).

Musculoskeletal Boundaries of the Lesser Pelvis

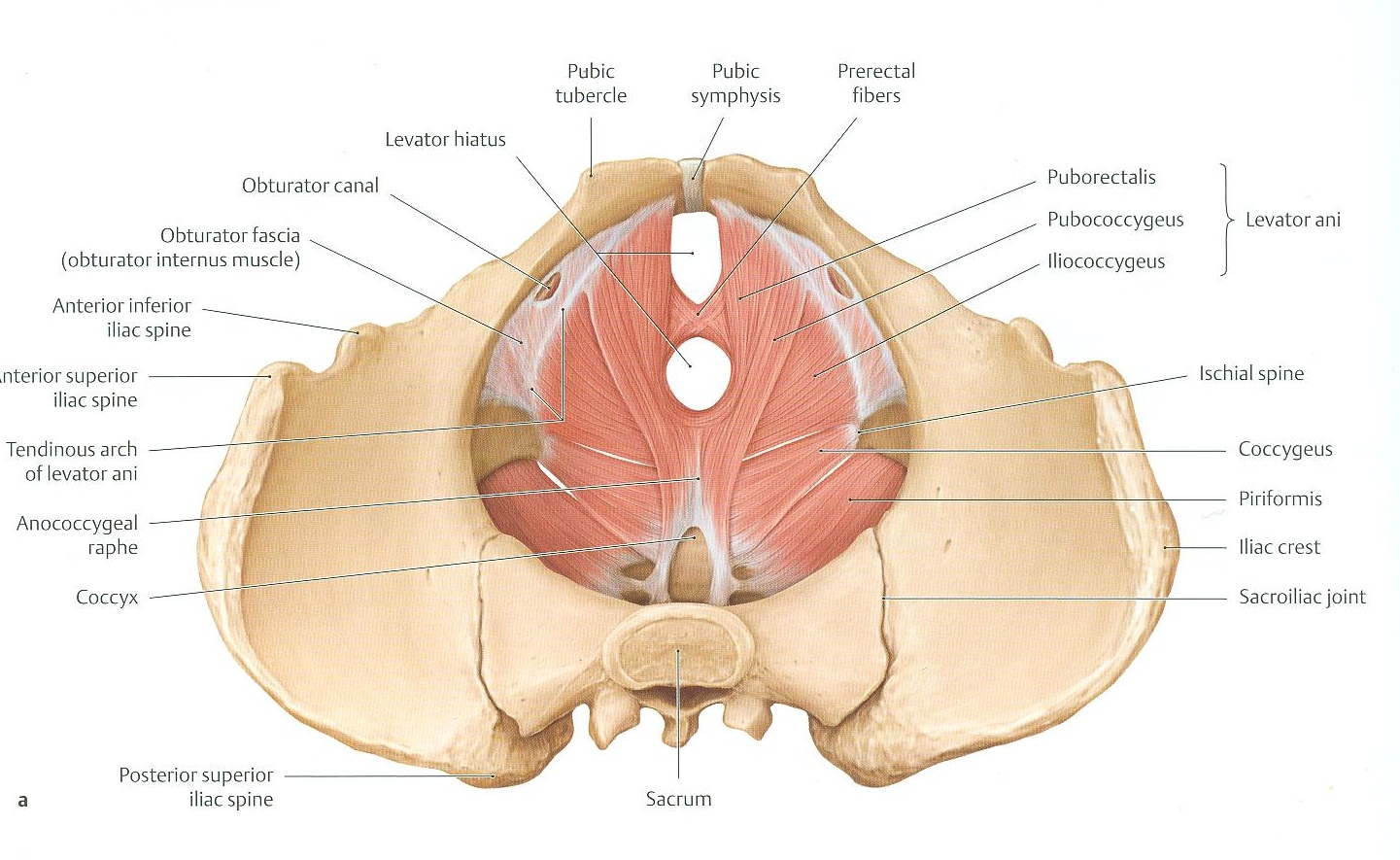

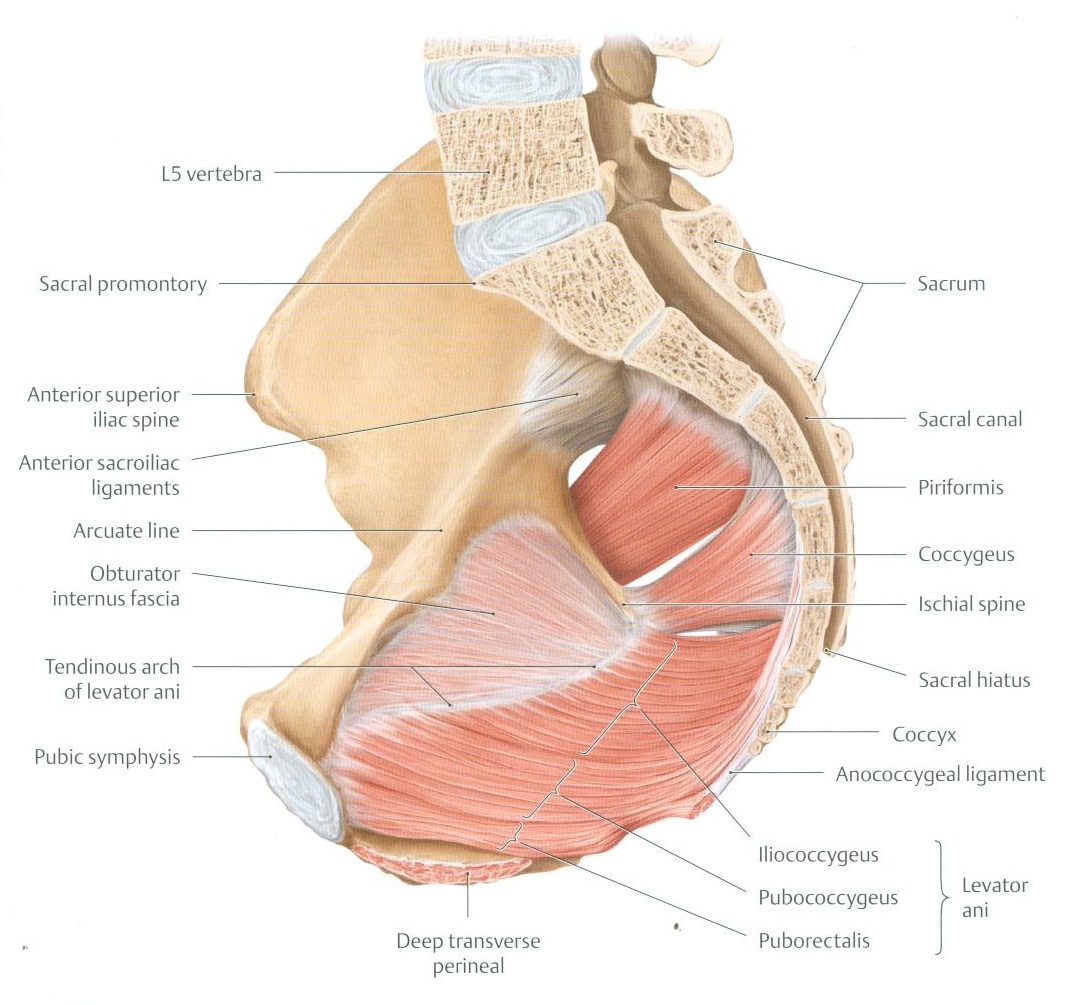

- Using an articulated bony pelvis with the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, examine the walls of the lesser pelvis. The posterolateral wall comprises the pelvic (anterior) surface of the sacrum and the muscular contents of the greater sciatic foramen, i.e., the piriformis muscle (Figure 3.11). Place one end of a wet paper towel on the lateral border of the sacrum, passing the other end through the greater sciatic foramen. This towel represents the piriformis muscle, with its tendon passing out through the greater sciatic foramen.

- The anterolateral wall of the lesser pelvis comprises (on each side) the body of the pubic bone, the obturator foramen and the bones

forming its margin, the body of the ischium, and the muscular contents of the lesser sciatic foramen, i.e., the obturator internus muscle (Figure 3.11), which also covers over the obturator foramen from the inside. Pass one hand through the pelvic inlet and cover the obturator foramen from the inside. This is where you will place one end of a second wet paper towel, replacing your hand with it. Pass the other end through the lesser sciatic foramen. This towel represents the obturator internus muscle, with its tendon passing out through the lesser sciatic foramen.

- Identify the pelvic outlet (inferior pelvic aperture), which is the inferior opening not filled in with paper towel. The pelvic outlet is bounded on each side by the:

- Inferior end of the pubic symphysis

- Ischiopubic ramus

- Ischial tuberosity

- Sacrotuberous ligament

- Tip of the coccyx

- Examine the superior border of the ala of the ilium, called the iliac crest. The iliac crest extends from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) anteriorly to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) posteriorly. Identify these features on the articulated bony pelvis.

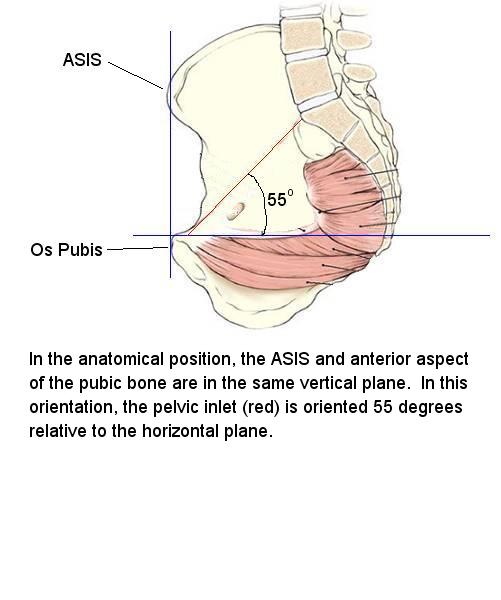

- In the erect posture, i.e., the anatomical position, the anterior superior iliac spines and the superior end of the pubic symphysis lie in the same vertical plane. Hold the articulated bony pelvis in the anatomical position. Observe that, in this position, the plane of the pelvic inlet forms an angle of approximately 55° to the horizontal plane (See Figure).

- While still holding the articulated bony pelvis in the anatomical position, observe that the posterolateral wall of the lesser pelvis, consisting of the pelvic surface of the sacrum, the greater sciatic foramina and the piriformis muscles, is well superior to the anterolateral wall, consisting of the pubic bones, a portion of the ischii, the obturator internus muscles and the lesser sciatic foramina. Because this is the orientation of the pelvis in the erect position, the anterolateral wall biomechanically constitutes a weight-bearing floor rather than a wall of the pelvic cavity.

- Note that all structures that exit the lesser pelvis, which originate from the posterolateral wall (except for the obturator artery), exit the lesser pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen. These structures include the piriformis muscle and tendon, nerves derived from the lumbosacral plexus, and exiting arteries. In contrast, structures that exit the lesser pelvis, which originate from the anterolateral wall, exit the lesser pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen (namely, the obturator internis tendon). The lesser sciatic foramen also serves as the doorway to the perineum. We will later encounter neurovascular structures that enter the perineum by passing in through the lesser sciatic foramen.

- While using the articulated bony pelvis with the two towels in place as references, examine the pelvic cavity in a prosected cadaveric pelvis. Attempt to identify the obturator internus muscle in the cadaver. If identification of the obturator internis muscle is difficult, recall that the proximal attachment of the obturator internis muscle is the inner border of the obturator foramen. To locate the obturator foramen, identify the pubic symphysis (remember that the pelvis has been bisected in the midline) and the pubic crest. Follow the pubic crest laterally to find the superior pubic ramus, which is the superior margin of the obturator foramen. The muscle directly inferior and partially attached to the superior pubic ramus is the obturator internis muscle.

- Attempt to identify the piriformis muscle in the cadaveric pelvis (Figure 3.11). If identification of the piriformis muscle is difficult, recall that the proximal attachment of the piriformis muscle is the lateral border of the sacrum. Look for the sectioned midline of the sacrum and trace the pelvic surface of the sacrum laterally to locate the piriformis muscle. An important relation of the piriformis muscle is the sacral plexus, a series of nerves (ventral rami of the sacral spinal nerves actually) that exit the sacrum via the anterior sacral foramina. The nerves of the sacral plexus pass inferolaterally over the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle toward the greater sciatic foramen. The sacral plexus will be examined in more detail later but make an initial attempt to identify these nerves now.

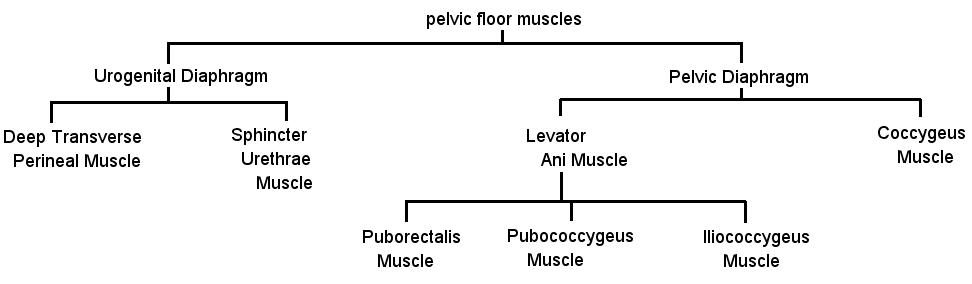

- The remaining muscles in the cadaveric pelvis contribute to the pelvic floor (Figure 3.11). The pelvic floor consists of a series of muscles (see Diagram) that close the pelvic outlet, allowing portions of the urinary, genital and alimentary tracts to pass. The majority of the pelvic outlet is closed by the pelvic diaphragm, except for a small anterior hiatus that's closed by the urogenital diaphragm (do not attempt to identify the urogenital diaphragm at this time).

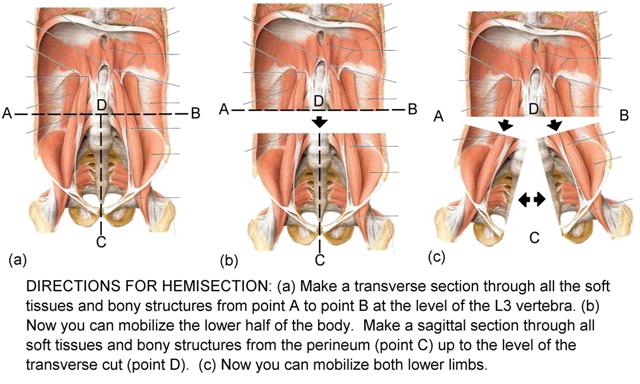

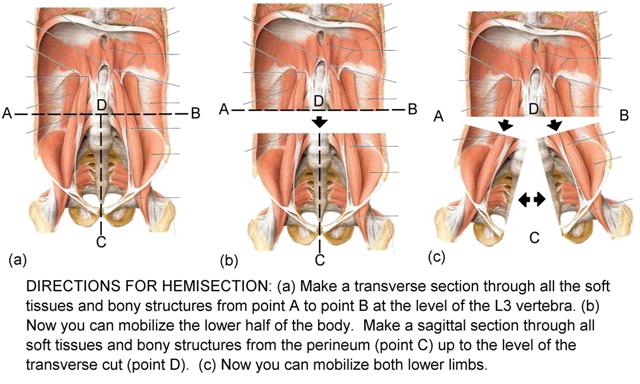

Preparation of the Pelvis

To begin this dissection sequence, the pelvis will be detached from the rest of the body. It has a tendency to dry out, and thus each pair of tables has a plastic container to store their pelvis in, between dissection laboratories. To detach the pelvis,

- Retrieve a carpenter saw from the drawer in the back of the room.

- Make a transverse cut 1cm superior to the intercristal line (you do not want to cut through the iliac crests).

- You should have a pelvis and lower limbs detached from the rest of the body.

- Make a transvers cut through each thigh, inferior enough so not to damage tissues of the perineum.

- When finished working with the pelvis, store it in the provided containers in fluid.

- When retrieving the specimens, allow them to drip excess fluid before moving them (avoid dripping on the floor), and place it INSIDE the body bag to work. Do not place the pelves on the on top of the body bag.

Inguinal Canal

- In the inguinal region, use blunt dissection to clean the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Gentle scraping motions with a dull scalpel blade yield good results. Be careful not to damage the spermatic cord (or round ligament of the uterus) where it emerges from the superficial inguinal ring.

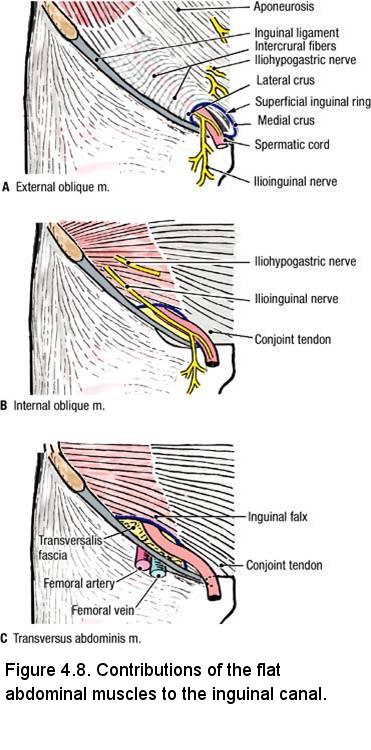

- Identify the superficial inguinal ring (Figure 4.8A), which is an opening in the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis.

- Identify the lateral (inferior) crus. The lateral crus is the portion of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis that forms the lateral margin of the superficial inguinal ring. It is attached to the pubic tubercle.

- Identify the medial (superior) crus. The medial crus is the portion of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis that forms the medial margin of the superficial inguinal ring. It is attached to the pubic crest.

- Identify the intercrural fibers. Intercrural fibers span across the crura superolateral to the superficial inguinal ring. They prevent the crura from spreading apart.

- At the margins of the superficial inguinal ring, observe the thin layer of fascia that extends from the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis onto the spermatic cord or round ligament of the uterus. This is the external spermatic fascia, which is the contribution of the external abdominal oblique muscle to the layers of the spermatic cord.

- Note that the ilioinguinal nerve emerges from the inguinal canal at the superficial inguinal ring, anterior (and perhaps a little lateral) to the spermatic cord (or round ligament of the uterus). The ilioinguinal nerve supplies sensory fibers to the skin on the anterior surface of the external genitalia and the medial aspect of the thigh. NOTE: Occasionally, the ilioinguinal nerve is completely absent.

- Identify the inguinal ligament. It is the inferior border of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Palpate the attachments of the inguinal ligament to the anterior superior iliac spine and to the pubic tubercle. Vessels and nerves exit the abdominal cavity and enter the lower limb by passing deep to the inguinal ligament.

- Use an illustration to study the lacunar ligament. The lacunar ligament is formed by the medial fibers of the inguinal ligament that turn posteriorly to attach to the pecten pubis (pectineal line).

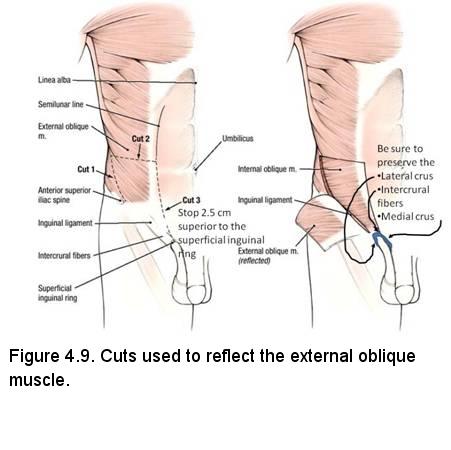

- Using scissors, make an incision from the medial end of cut 2 (see Figure) to a point 2.5 cm from the superior margin of the superficial inguinal ring (Figure 4.9, left-side, cut 3). DO NOT CUT THROUGH THE INTERCRURAL FIBERS (APEX) OF THE SUPERCIAL INGUINAL RING. Cut 3 should follow the lateral side of the semilunar line and cut only the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis.

- Reflect the external abdominal oblique muscle in an inferior and lateral direction to reveal the lower half of the internal abdominal oblique muscle (Figure 4.9, right-side).

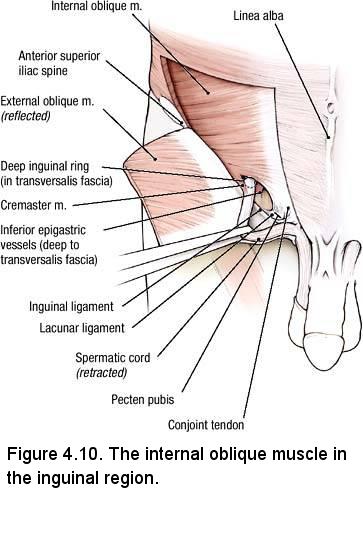

- Identify the internal abdominal oblique muscle. Observe the portion of the internal abdominal oblique muscle that arises from the lateral part of the inguinal ligament (Figure 4.10). Note that this portion of the internal abdominal oblique muscle arches medially and attaches to the pecten pubis. It contributes to the roof of the inguinal canal.

- Lateral to the spermatic cord (or round ligament of the uterus), observe muscle fibers connecting the internal abdominal oblique muscle to

the spermatic cord (or round ligament of the uterus) (Figure 4.10). This is the layer of cremaster muscle and fascia, which is the contribution of the internal abdominal oblique muscle to the coverings of the spermatic cord in the male. In the female, the cremaster muscle and fascia surround the round ligament of the uterus. The cremaster muscle is supplied by the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. The genitofemoral nerve arises from the lumbar plexus and will be studied in the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity prosection.

- In the intermuscular plane between the external abdominal oblique and the internal abdominal oblique muscles, look for two nerves (Figure 4.8B):

- Ilioinguinal nerve courses through the inguinal canal to emerge at the superficial inguinal ring.

- Iliohypogastric nerve runs parallel to the ilioinguinal nerve and superior to it, outside of the inguinal canal.

- Just medial to the superficial inguinal ring, the aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique becomes fused with the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle to form the conjoint tendon (Figure 4.10). Dissection Note: Inferiorly, the transversus abdominis muscle is often difficult to separate from the internal abdominal oblique muscle because their tendons are fused near their distal attachments (conjoint tendon), and the muscle bellies adhere to each other laterally. You do not have to separate the internal abdominal oblique muscle from the transverses abdominis muscle.

Dissection Overview: Scrotum, Testis, and Spermatic Cord (TABLES WITH FEMALE CADAVERS ARE STILL RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS ANATOMY)

Dissection Instructions: Spermatic Cord

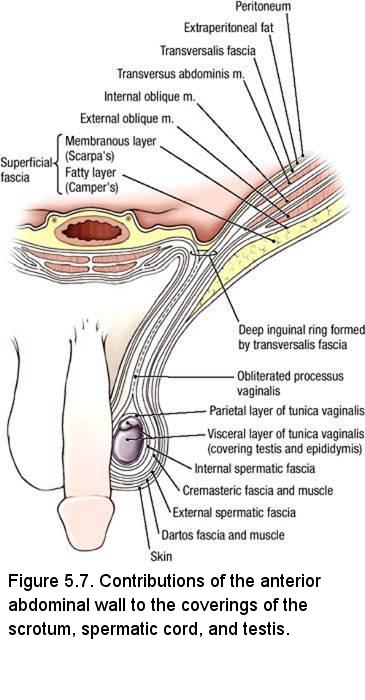

The spermatic cord contains the ductus deferens, testicular vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. The contents of the spermatic cord are surrounded by three fascial layers, the coverings of the spermatic cord, which are derived from layers of the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 5.7). These coverings are added to the spermatic cord as it passes through the inguinal canal.

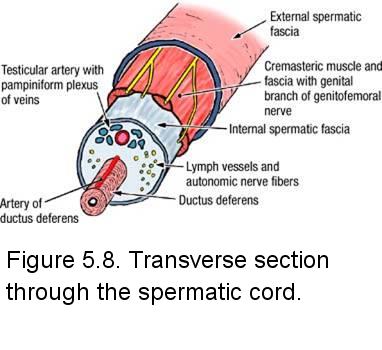

- Study an illustration of a transverse section through the spermatic cord (Figure 5.8).

- Palpate the ductus deferens (vas deferens) within the spermatic cord. It is hard and cord-like.

- The three coverings of the spermatic cord are fixed to each other at the time of embalming and cannot be separated. The coverings of the spermatic cord are (Figure 5.8):

- External spermatic fascia - derived from the external abdominal oblique muscle

- Cremasteric muscle and fascia - derived from the internal abdominal oblique muscle

- Internal spermatic fascia - derived from the transversalis fascia

- Use a probe to separate the ductus deferens from the pampiniform plexus of veins.

- See if you can locate the artery of the ductus deferens (it arises from the inferior vesicle artery), a small vessel located on the surface of the ductus deferens (Figure 5.8)

- Follow the ductus deferens superiorly into the inguinal canal and toward the deep inguinal ring. Note that the ductus deferens passes through the deep inguinal ring lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels.

- Identify the testicular artery from the pampiniform plexus of veins. The testicular artery can be distinguished from the veins by its slightly thicker wall.

- Note that sensory nerve fibers, autonomic nerve fibers, and lymphatic vessels accompany the blood vessels in the spermatic cord (Figure 5.8), but they are too small to dissect.

IN THE CLINIC: Vasectomy

The ductus deferens can be surgically interrupted in the superior part of the scrotum (vasectomy). Sperm production in the testis continues but the spermatozoa cannot reach the urethra.

The ductus deferens can be surgically interrupted in the superior part of the scrotum (vasectomy). Sperm production in the testis continues but the spermatozoa cannot reach the urethra.

Dissection Instructions: Testis

- Use your fingers to free the testis and spermatic cord from the scrotum.

- Observe that the visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis covers the anterior, medial, and lateral surfaces of the testis, but not its posterior surface.

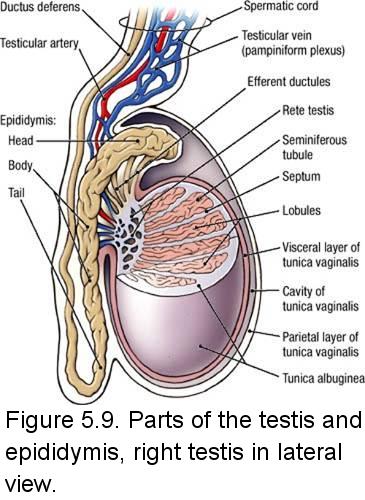

- Use a probe to trace the ductus deferens inferiorly until it joins the epididymis. Identify the tail, body, and head of the epididymis (Figure 5.9).

- Note that the testis has been sectioned longitudinally from its superior pole to its inferior pole, along its anterior surface. Use the epididymis as a hinge, and open the halves of the testis like opening a book.

- Note the thickness of the tunica albuginea, which is the fibrous capsule of the testis. Observe the septa that divide the interior of the testis into lobules (Figure 5.9).

- Use a needle or fine-tipped forceps to tease some of the seminiferous tubules out of one lobule.

IN THE CLINIC: Lymphatic Drainage of the Testis

Lymphatics from the scrotum drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Inflammation of the scrotum may cause tender, enlarged superficial inguinal lymph nodes. In contrast, lymphatics from the testis follow the testicular vessels through the inguinal canal and into the abdominal cavity where they drain into lumbar (lateral aortic) nodes and preaortic lymph nodes. Testicular tumors may metastasize to lumbar and preaortic lymph nodes, not to superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Lymphatics from the scrotum drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Inflammation of the scrotum may cause tender, enlarged superficial inguinal lymph nodes. In contrast, lymphatics from the testis follow the testicular vessels through the inguinal canal and into the abdominal cavity where they drain into lumbar (lateral aortic) nodes and preaortic lymph nodes. Testicular tumors may metastasize to lumbar and preaortic lymph nodes, not to superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Dissection Overview: Gluteal Region

Dissection Instructions: Gluteal Region

- Turn the cadaver to the prone position.

- Get a cadaveric pelvis from the cabinet. Review the location of the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. The lesser sciatic foramen is between these two ligaments.

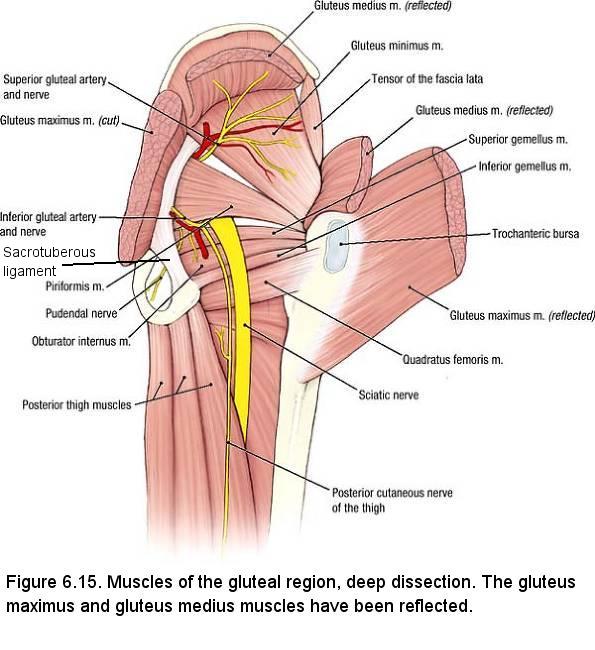

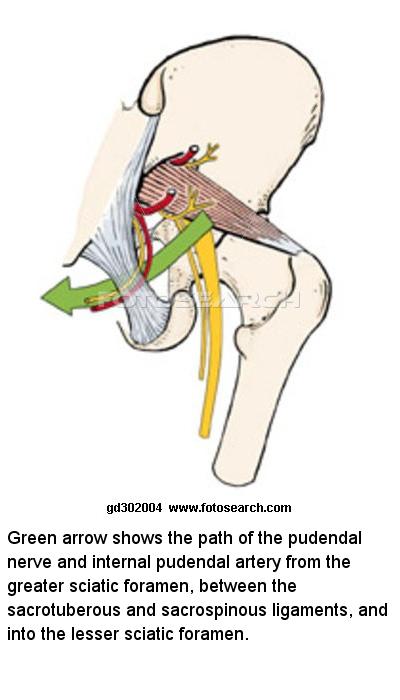

- Recall that the sciatic nerve, posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, inferior gluteal nerve, inferior gluteal artery and vein exit the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen and enter the gluteal region by passing under the inferior border of the piriformis muscle. The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal artery and vein also exit the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen, passing inferior to piriformis muscle.

- Dissect the internal pudendal artery and vein, and pudendal nerve near the medial end of the inferior border of the piriformis muscle (Figure 6.15).

- Follow the internal pudendal artery and pudendal nerve to where they pass anterior to the sacrotuberous ligament and posterior to the sacrospinous ligament (See Figure). If necessary, open a window in the sacrotuberous ligament by passing a probe deep to the ligament (be certain that the probe is superficial to the internal pudendal artery and pudendal nerve) and use a scalpel to cut through the sacrotuberous ligament down to the probe. Identify the sacrospinous ligament anterior to the artery and nerve.

- After passing through the lesser sciatic foramen, the internal pudendal artery and pudendal nerve enter the perineum (See Figure). The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal artery and vein will be traced into the pudendal canal (Alcock's Canal).

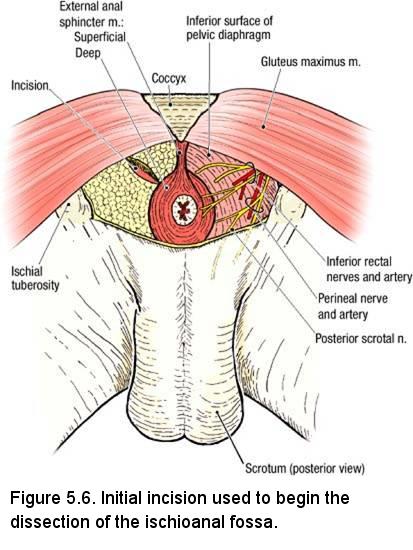

Dissection Overview: Anal Triangle and Ischioanal Fossa

The order of dissection will be as follows: Dissection of the anal triangle will begin with removal of skin covering the ischioanal fossa. The nerves and vessels of the ischioanal fossa will be dissected. The fat will be removed from the ischioanal fossa to reveal the inferior surface of the pelvic diaphragm.

Dissection Instructions: Anal Triangle and Ischioanal Fossa

The following will be performed in both male and female cadavers. The ischioanal (ischiorectal) fossa is a wedge-shaped area on either side of the anus. The apex of the wedge is directed superiorly and the base is beneath the skin. The ischioanal fossa is filled with fat that helps accommodate the fetus during childbirth or the distended anal canal during the passage of feces. The ischioanal fat is part of the superficial fascia of this region. The goal of this dissection is to remove the fat and identify the nerves and vessels that pass through the ischioanal fossa. The following figures depict a male, but the dissection procedure is the same for a female.

- Skin the anal triangle. Be careful when skinning around the anus because a portion of the external anal sphincter muscle is in contact with the skin.

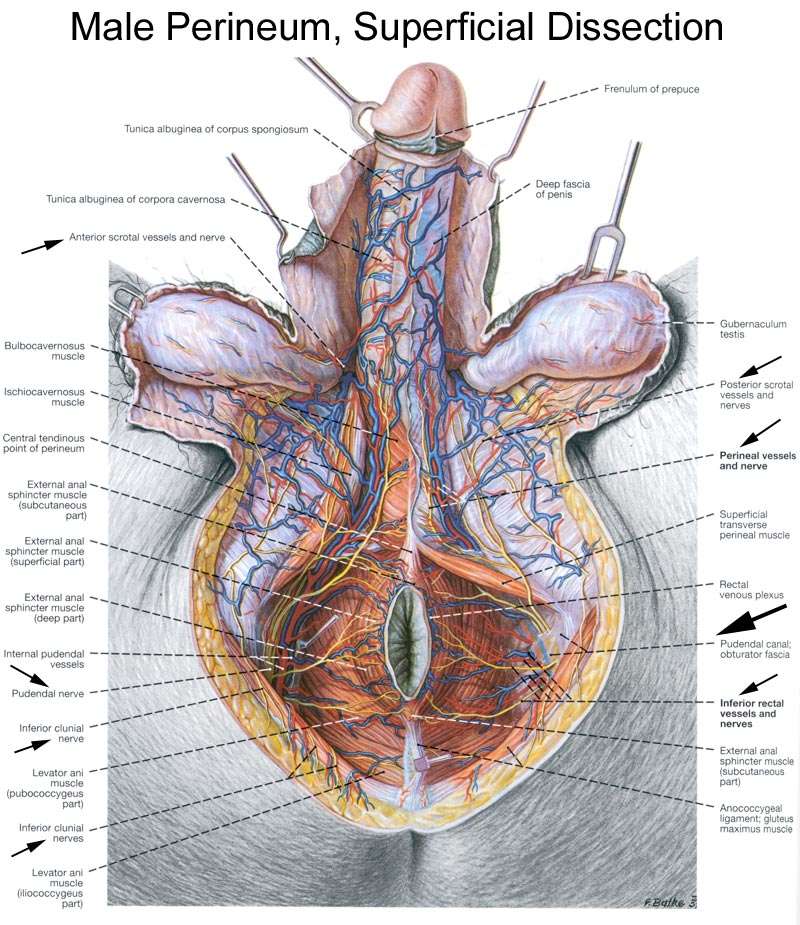

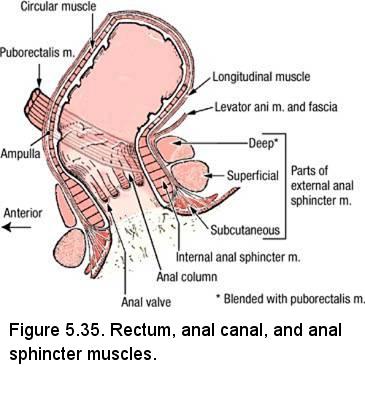

- Use blunt dissection to clean the external anal sphincter muscle (Figure 5.6). The external anal sphincter muscle has three parts (YOU DO NOT HAVE TO DISTINGUISH THESE - BUT DO KNOW HOW THE SPHINCTER IS ORGANIZED):

- Subcutaneous - encircling the anus (undoubtedly removed when you skinned the area)

- Superficial - anchoring the anus to the perineal body and coccyx

- Deep - a circular band that is fused with the pelvic diaphragm

- Lateral to the anus, insert closed scissors into the ischioanal fat to a depth of 3 cm. Open the scissors in the transverse direction to tear the fat (Figure 5.6, incision on the left side).

- Insert your finger into the incision and carefully move it back and forth (medial to lateral) to enlarge the opening. The fat may be dense. Use a blunt object to break up the fat and remove it piecemeal. If you use a scalpel to remove the fat your will inadvertently damage the inferior rectal vessels and nerves

- Palpate the inferior rectal (anal) nerve, arteries, and veins (Figure 5.6, right side). Preserve the branches of the inferior rectal nerve and vessels but use blunt dissection to remove the fat that surrounds them. Dry the area with towels if necessary.

- Use blunt dissection to clean the inferior surface of the pelvic diaphragm (the medial boundary of the ischioanal fossa).

- Use blunt dissection to clean the fascia of the obturator internus muscle (obturator internus fascia). Observe that the obturator internus muscle forms the lateral wall of the ischioanal fossa.

- Observe that the inferior rectal nerve and vessels penetrate the fascia of the obturator internus muscle to enter the ischioanal fossa.

- Place gentle traction on the inferior rectal vessels and nerves and observe that a ridge is raised in the obturator internus fascia. The potential space deep to this ridge is called the pudendal canal. Carefully incise the obturator fascia along this ridge to open the pudendal canal. The pudendal canal is a specialization of the fascia of the obturator internus muscle.

- Use a probe to elevate and clean the contents of the pudendal canal. The pudendal canal contains the pudendal nerve and the internal pudendal artery and vein.

NOTE: The pudendal nerve gives rise to the inferior rectal, perineal and dorsal nerves of the penis or clitoris. You dissected the inferior rectal nerve and should appreciate that it supplies the external anal sphincter, the lining of the lower part of the anal canal, and the circumanal skin. The perineal nerve gives rise to posterior scrotal or labial and muscular branches to the superficial and deep transverse perinei, bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and sphincter urethrae muscles. The dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris supplies the corpus spongiosum. In males it runs on the dorsum of the penis to end in the glans penis. In females the dorsal nerve of the clitoris is very small.

Overview

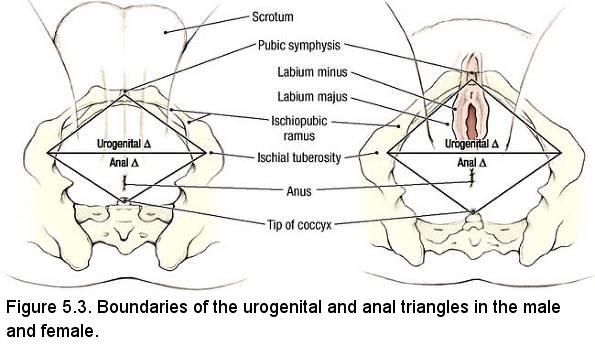

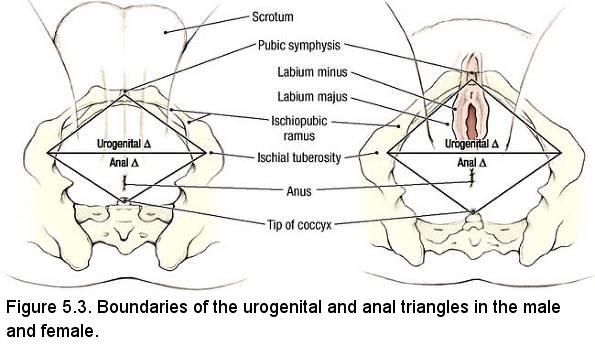

The perineum is a diamond-shaped area between the upper thighs and between the lower parts of the buttocks. It consists of structures that constitute the region below the pelvic floor. The perineum is bounded by the pubic symphysis anteriorly, the coccyx posteriorly, and the two ischial tuberosities laterally. Between the pubic symphysis and ischial tuberosities are the rami of the pubic bone and the rami of the ischia (since it is difficult to demarcate where the inferior ramus of the pubic bone ends and the ischial ramus begins, it is common parlance to call these structures "ischiopubic rami"). Extending from the ischial tuberosities to the coccyx (and sacrum) are the sacrotuberous ligaments. For descriptive purposes, the diamond-shaped perineum is divided into two triangles (Figure 5.3). The anal triangle is the posterior part of the perineum and it contains the anal canal and anus and has already been dissected. The urogenital triangle is the anterior part of the perineum and contains the urethra and the external genitalia. At the outset of dissection, it is important to understand that the pelvic diaphragm separates the pelvic cavity from the perineum (Figure 5.1).

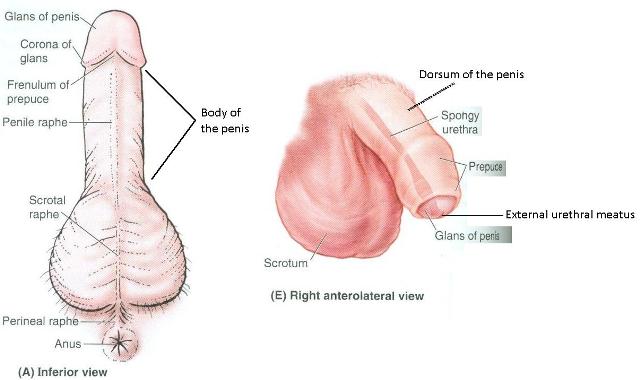

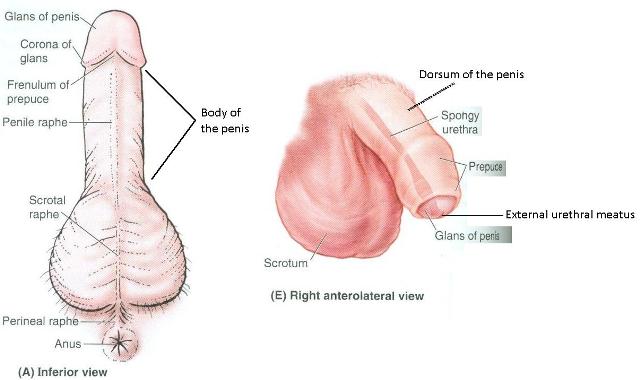

Surface Anatomy of the Male Genitalia

Because of the variability of the genitalia of the cadavers, and the fact that as the dissection of this area progresses the surface anatomy of the genitalia will be compromised, a male and female cadaver will be placed in the dissection laboratory specifically for surface anatomy study.

- Penis

- Prepuce (foreskin) - note: if your cadaver has a circumcised penis, it will not have a prepuce. Find a cadaver that does. We will write the numbers of the lucky tables on the blackboards.

- Frenulum of the prepuce

- Glans of the penis

- Corona of the penis

- External urethral meatus (orfice)

- Body of the penis

- Dorsum of the penis

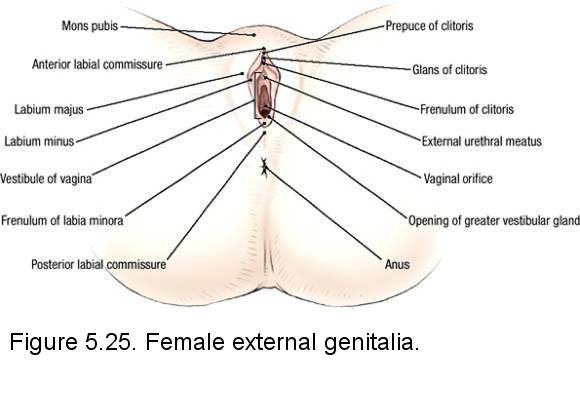

Surface Anatomy of the Female Genitalia

- Mons pubis

- Labia majora

- Prepuce (foreskin) of the clitoris

- Glans of the clitoris

- Labia minora

- Vestibule

- area between the labia minora - External urethral orfice

- Vaginal orfice (introitus)

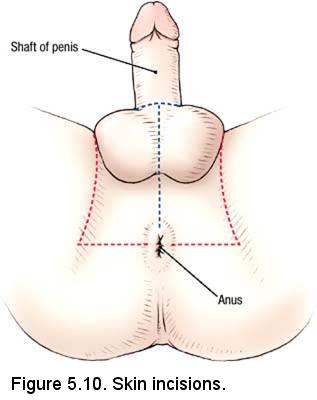

Dissection Overview: Male Urogenital Triangle

Dissection Instructions: Skin Removal

- Partner with a dissection team that has a female cadaver for the following dissection. You are expected to know the anatomical details for both sexes.

- Place the cadaver (mobilized limb) in the supine position.

- Make a skin incision that encircles the proximal end of the penis (Figure 5.10, blue dashed lines). Make the skin incisions along the margins of the urogenital triangle indicated by the red lines in Figure 5.10. Remove only the skin (the skin is very thin).

- If the cadaver has a large amount of fat in the superficial fascia of the medial thighs, remove a portion of the superficial fascia starting at the ischiopubic ramus and extending down the medial thigh about 7 cm. Stay superficial to the deep fascia when removing the superficial fascia.

- The posterior scrotal nerves and arteries, which enter the urogenital triangle by passing lateral to the external anal sphincter muscle (Figure). The posterior scrotal nerves and arteries supply the posterior part of the scrotum. The posterior scrotal nerves and arteries are terminal branches of the perineal nerve and artery.

Dissection Instructions: Superficial Perineal Pouch

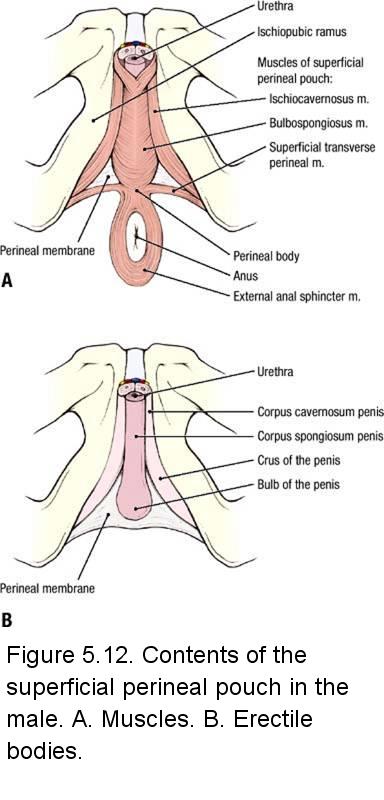

- The contents of the superficial perineal pouch in the male are three paired muscles (superficial transverse perineal muscle, bulbospongiosus muscle, and ischiocavernosus muscle), the crura of the penis, and the bulb of the penis (Figure 5.12A,B). The superficial perineal pouch also contains the branches of the perineal arteries, veins, and nerves that supply these structures.

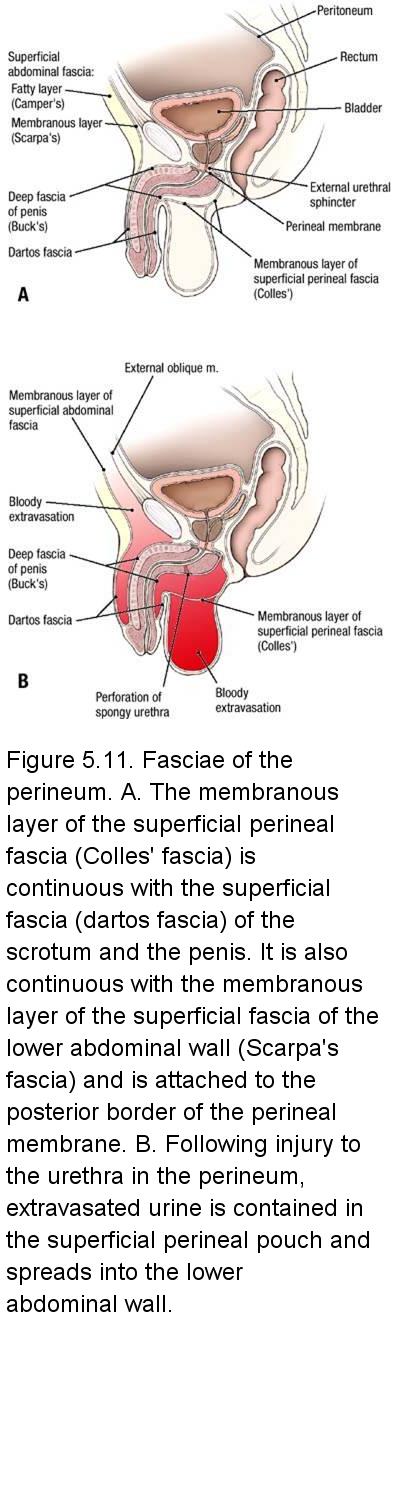

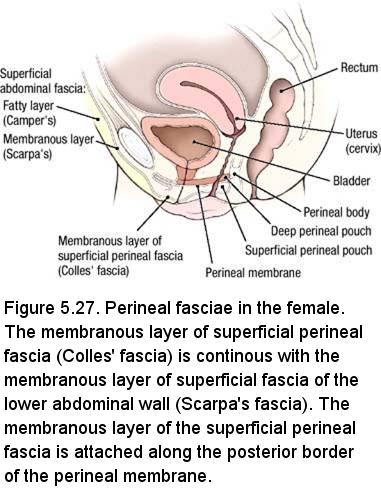

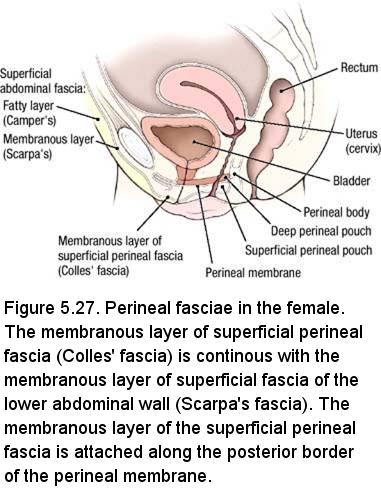

- It is not necessary to identify the membranous layer of the superficial perineal fascia (Colles' fascia) to complete the dissection. Use a probe to dissect through the superficial perineal fascia in the midline.

- Use blunt dissection to find the bulbospongiosus muscle in the midline of the urogenital triangle anterior to the anus. The two muscles are joined by a longitudinal raphe. Their fibers arise from both the central tendon and the raphe and diverge around the bulb of the penis. The posterior fibers expel the last drops of urine or semen from the penile urethra, while the intermediate and anterior fibers help maintain penile erection by tightening the fascia covering the deep dorsal vein. (Figure 5.12A). Use a probe to clean the surface of the bulbospongiosus muscle (note that it is very thin).

- Lateral to the bulbospongiosus muscle, use a probe to clean the surface of the ischiocavernosus muscle (Figure 5.12A). The ischiocavernosus muscle covers the superficial surface of the crus of the penis. The proximal attachment of the ischiocavernosus muscle is the ischial tuberosity and the ischiopubic ramus. The distal attachment of the ischiocavernosus muscle is the crus of the penis. The ischiocavernosus muscle forces blood from the crus of the penis into the distal part of the corpus cavernosum penis and helps to maintain erection.

- Using blunt dissection, attempt to find the superficial transverse perineal muscle at the posterior border of the urogenital triangle (Figure 5.12A). The superficial transverse perineal muscle may be delicate and difficult to find; limit the time spent looking for it. The lateral attachments of the superficial transverse perineal muscle are the ischial tuberosity and the ischiopubic ramus. The medial attachment of the superficial transverse perineal muscle is the perineal body. The perineal body is a fibromuscular mass located anterior to the anal canal and posterior to the perineal membrane that serves as an attachment for several muscles. The superficial transverse perineal muscle fixes and stabilizes the perineal body.

- Use a probe to dissect between the three muscles of the superficial perineal pouch until a small triangular opening is created (Figure 5.12A). The membrane that becomes visible through this opening is the inferior fascia of the urogential diaphragm (perineal membrane). The perineal membrane is the deep boundary of the superficial perineal pouch and the superficial boundary of the deep perineal pouch (i.e., the perineal membrane separates the superficial and deep perineal pouches). The bulb and crura of the penis are attached to the perineal membrane.

- Examine the right and left bulbospongiosus muscles. Typically, one side is better than the other. Decide which side is a better specimen, and remove the bulbospongiosus muscle from the other side to expose the underlying bulb of the penis.

- Identify the bulb of the penis on the side in which the bulbospongiosus muscle has been removed (Figure 5.12B). The bulb of the penis is continuous with the corpus spongiosum penis and contains a portion of the spongy urethra.

- Examine the cleaned right and left ischiocavernosus muscles. Examine the right and left ischiocavernosus muscles. Typically, one side is better than the other. Decide which side is a better specimen, and remove the ischiocavernosus muscle from the other side to expose the underlying crus of the penis (L. crus, a leg-like part; pl. crura). (Figure 5.12B)

- Identify the crus of the penis. The crus of the penis is the proximal part of the corpus cavernosum penis.

IN THE CLINIC: Superficial Perineal Pouch

If the urethra is injured in the perineum, urine may escape into the superficial perineal pouch. The urine may spread into the scrotum and penis, and upward into the lower abdominal wall between the membranous layer of the abdominal superficial fascia (Scarpa's fascia) and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle (Figure 5.11B). The urine does not enter the thigh because the membranous layer of the superficial fascia attaches to the fascia lata, ischiopubic ramus, and posterior edge of the perineal membrane.

If the urethra is injured in the perineum, urine may escape into the superficial perineal pouch. The urine may spread into the scrotum and penis, and upward into the lower abdominal wall between the membranous layer of the abdominal superficial fascia (Scarpa's fascia) and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle (Figure 5.11B). The urine does not enter the thigh because the membranous layer of the superficial fascia attaches to the fascia lata, ischiopubic ramus, and posterior edge of the perineal membrane.

Dissection Instructions: Penis

- Remove the skin from the body of the penis, detaching it around the corona of the glans (Figure). Do not skin the glans.

- Use a probe to dissect the superficial dorsal vein of the penis. The superficial dorsal vein of the penis drains into the superficial external pudendal vein of the inguinal region.

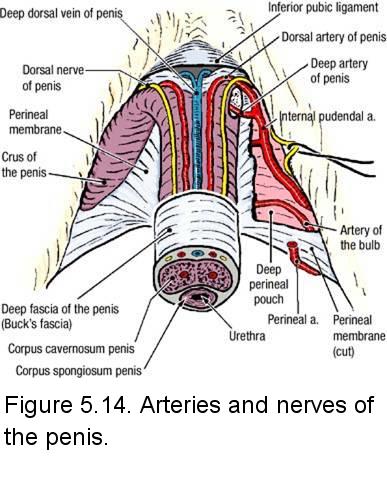

- On the dorsum of the penis, use a probe to dissect through the deep fascia of the penis and identify (Figure 5.14):

- Deep dorsal vein of the penis - a single vein in the midline (it may be split longitudinally when the penis is later bisected; alternatively, it may be found on only one side of the penis or the other). Most of the blood from the penis drains through the deep dorsal vein of the penis into the prostatic venous plexus.

- Dorsal artery of the penis (right and left) - one artery on each side of the deep dorsal vein. The dorsal artery of the penis is a terminal branch of the internal pudendal artery.

- Dorsal nerve of the penis (right and left) - one nerve on each side of the midline, lateral to the dorsal artery of the penis. The dorsal nerve of the penis is a branch of the pudendal nerve.

- Use a probe to trace the vessels and nerves of the penis proximally. Use an illustration to study the course of the pudendal nerve and the internal pudendal artery (Figure 5.14). Observe that the dorsal artery and nerve of the penis course deep to the perineal membrane before they emerge onto the dorsum of the penis. The deep dorsal vein passes between the inferior pubic ligament and the anterior edge of the perineal membrane to enter the pelvis. Note that the deep dorsal vein does not accompany the dorsal artery of the penis and dorsal nerve of the penis proximal to the body of the penis.

Overview: Deep Perineal Pouch / Urogenital (UG) Diaphragm

- Use an illustration to study the following:

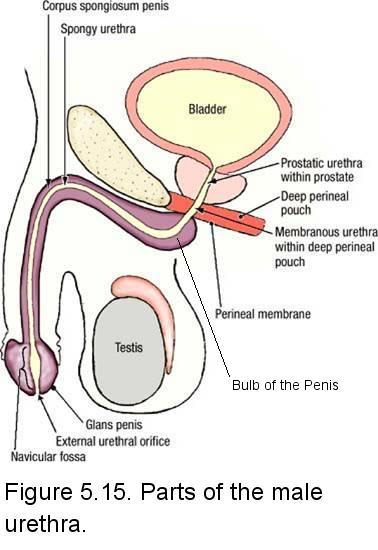

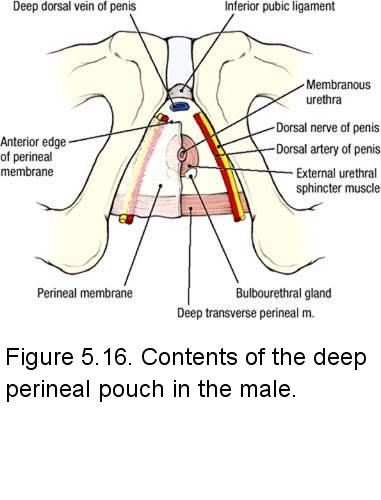

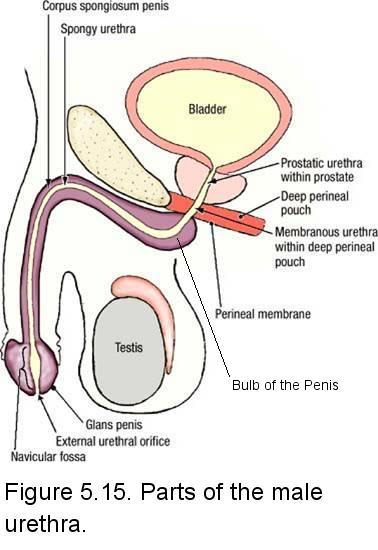

- Membranous urethra - extends from the perineal membrane to the prostate gland (Figure 5.15). This is the shortest (about 1 cm), thinnest, narrowest, and least distensible part of the urethra.

- External urethral sphincter (sphincter urethrae) muscle - a voluntary muscle that surrounds the membranous urethra (Figure 5.16). When the external urethral sphincter muscle contracts, it compresses the membranous urethra and stops the flow of urine.

- Deep transverse perineal muscle - has a lateral attachment to the ischial tuberosity and the ischiopubic ramus and a medial attachment to the perineal body (Figure 5.16). Its fiber direction and function are identical to those of the superficial transverse perineal muscle, which is a content of the superficial perineal pouch.

- The bulbourethral glands (of Cowper) are located in the deep perineal pouch lateral to the membranous urethra. The duct of the bulbourethral gland passes through the perineal membrane and drains into the proximal portion of the spongy urethra.Upon erotic stimulation these glands secrete a mucoid secretion that precedes ejaculation.

- The deep perineal pouch contains branches of the pudendal nerve and internal pudendal artery. These structures supply the external urethral sphincter muscle, the deep transverse perineal muscle, and the penis (Figure 5.16).

- Collectively, the muscles within the deep perineal pouch plus the perineal membrane are known as the urogenital diaphragm. This older anatomical nomenclature is still in clinical use.

Dissection Review

- Return the muscles of the urogenital triangle to their correct anatomical positions.

- Review the contents of the male superficial perineal pouch. Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and view the contents of the superficial perineal pouch.

- Use an illustration to review the course of the internal pudendal artery from its origin in the pelvis to the dorsum of the penis.

- Use an illustration to review the course and branches of the pudendal nerve.

- Study an illustration showing the course of the deep dorsal vein of the penis into the pelvis to join the prostatic venous plexus.

- Draw a cross section of the penis showing the erectile bodies, superficial fascia, deep fascia, vessels, and nerves.

- Obtain an illustration that shows the entire male urethra and review its parts.

Dissection Overview: Female Urogenital Triangle (TABLES WITH MALE CADAVERS ARE STILL RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS ANATOMY)

The order of dissection of the female urogenital triangle will be as follows: The external genitalia will be examined. The superficial perineal fascia will be removed and the contents of the superficial perineal pouch will be identified. The contents of the deep perineal pouch will be described, but not dissected.

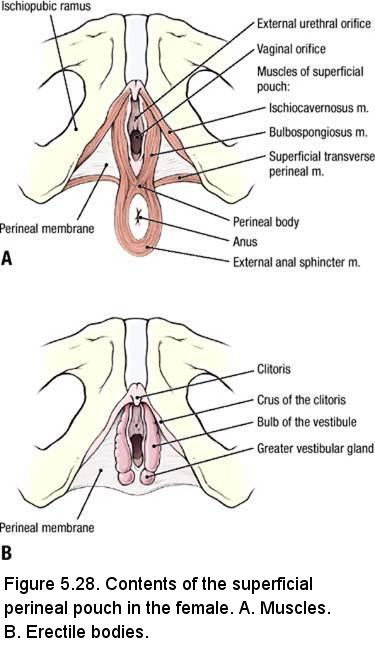

Dissection Instructions: Superficial Perineal Pouch and Clitoris

- Place the pelvis in the supine position

- Make an incision in the skin fold of the groin, that is, where the lateral aspects of the labia majora (hair-covered outer folds of the female external genitalia) meet the thigh.

- From the incision and using blunt dissection as much as possible, roll the cut edge of the labial skin anteriorly and medially. This

will preserve the rest of the external genitalia - labia minora, glans clitoridis, vaginal opening, etc., but allow you to study the structures of the superficial pouch

- The bulbospongiosus muscles (Figure 5.28A) are lateral to the labia minora and encircle the vaginal opening. Locate the vaginal opening. Using the index finger and thumb, insert one digit into the vaginal opening and palpate between the thumb and index finger the bulb of the vestibule covered superficially by the bulbospongiosus muscles. It is not a very robust structure. Expose the bulbospongiosus muscles by gently removing the fat and fascia You may see the posterior labial nerves and arteries. Other small branches of the perineal nerve and artery supply the muscles of the urogenital triangle. The perineal nerve and artery are branches of the pudendal nerve and internal pudendal artery, respectively.

- The ischiocavernosus muscles (Figure 5.28A) cover the superficial surfaces of the crura of the clitoris (L. crus, a

leg-like part; pl. crura) (Figure 5.28B). The crus of the clitoris is the proximal part of the corpus cavernosum clitoris.

The two corpora cavernosa form the body of the clitoris.

The proximal attachments of the ischiocavernosus muscle are the ischial tuberosity and ischiopubic ramus. The distal attachment of the ischiocavernosus muscle is to the crus of the clitoris. Locate the clitoris and palpate the glans and the body of the clitoris. Realize that the crus of the clitoris is continuous with the corpus cavernosum clitoris and the two corpora cavernosa form the body of the clitoris.

To expose the ischiocavernosus muscle, gently, with blunt dissection, remove the fascia and fat along the ischiopubic ramus. Most times you will encounter a thick shiny dense fascia covering the ischiocavernosus muscle. When you remove this layer, the ischiocavernosus muscle fibers will be seen.

- Clean the fat and fascia between the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles to expose the triangular inferior surface of the

UG diaphragm, the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm (perineal membrane). The base of the triangle from the perineal body

(Figure 5.28A) (the median attachment of the bulbospongiosus muscles and superficial transverse perineal muscles) to the ischial tuberosity

is delineated by the superficial transverse perineal muscle (Figure 5.28A). This is a delicate muscle. DO NOT DISSECT IT. The lateral

attachment of the superficial transverse perineal muscle is the ischial tuberosity and the ischiopubic ramus. The medial attachment of the

superficial transverse perineal muscle is the perineal body. The perineal body is a fibromuscular mass located between the anal canal and

the posterior edge of the perineal membrane that serves as an attachment for several muscles. The superficial transverse perineal muscle

helps to support the perineal body.

Use a probe to dissect between the three muscles of the superficial perineal pouch until a small triangular opening is created. The membrane that becomes visible through this opening is the perineal membrane (Figure 5.28A). The perineal membrane is the deep boundary of the superficial perineal pouch and the superficial boundary of the deep perineal pouch (i.e., the perineal membrane separates the superficial and deep perineal pouches). The bulb of the vestibule and crura of the clitoris are attached to the perineal membrane. - Examine the cleaned right and left bulbospongiosus muscles. Reflect the worse of the two bulbospongiosus muscles from the bulb of the vestibule.

- Examine the cleaned right and left ischiocavernosus muscles. Reflect the worse of the two ischiocavernosus muscles from the crus of the clitoris.

- Examine the erectile tissues, the bulb of the vestibule (Figure 5.28B) and (one) crus of the clitoris. Anteriorly, the bulbs of the two sides are joined at the commissure of the bulbs and the commissure is continuous with the glans of the clitoris. Do not attempt to find the commissure of the bulbs.

- If possible, look for the greater vestibular gland (Figure 5.28B) immediately posterior to the bulb of the vestibule.

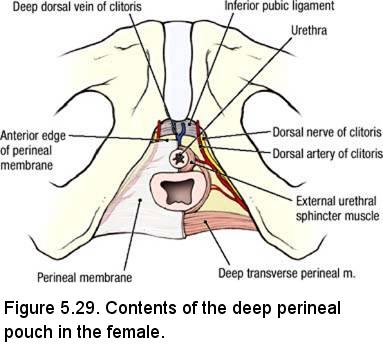

Overview: Deep Perineal Pouch / Urogenital (UG) Diaphragm

- Use an illustration to study the following:

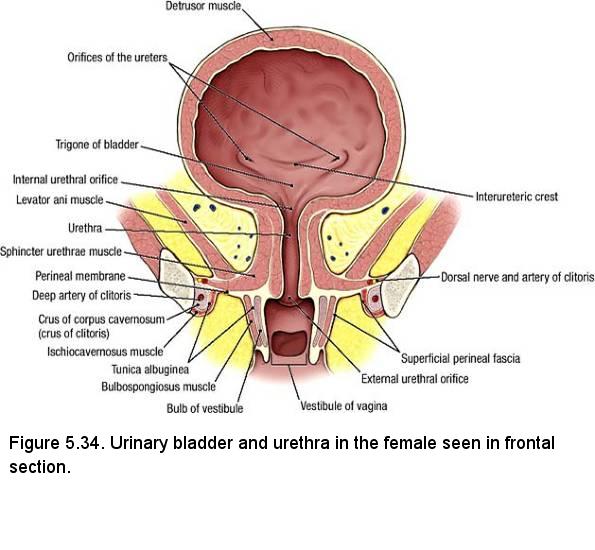

- Urethra - extends from the internal urethral orifice in the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice in the vestibule of the vagina (about 4 cm).

- External urethral sphincter (sphincter urethrae) muscle - a voluntary muscle that surrounds the urethra. When the external urethral sphincter muscle contracts, it compresses the urethra and stops the flow of urine.

- Deep transverse perineal muscle - has a lateral attachment to the ischial tuberosity and the ischiopubic ramus and a medial attachment to the perineal body. Its fiber direction and function are identical to those of the superficial transverse perineal muscle (which is a content of the superficial perineal pouch).

- Other contents of the deep perineal pouch include branches of the internal pudendal artery and branches of the pudendal nerve that supply the external urethral sphincter muscle, the deep transverse perineal muscle, and the clitoris (Figure 5.29).

- Collectively, the muscles within the deep perineal pouch plus the perineal membrane are known as the urogenital diaphragm. This older anatomical nomenclature is still in clinical use.

IN THE CLINIC: Obstetric Considerations

As the head of the baby passes through the vagina during childbirth, the anus and the levator ani muscle are forced posteriorly toward the sacrum and coccyx. The urethra is forced anteriorly toward the pubic symphysis. Perineal lacerations during childbirth are common, and it may be necessary to surgically widen the vaginal orifice (episiotomy). If the perineal body is lacerated, it must be repaired to prevent weakness of the pelvic floor, which could result in prolapse of the urinary bladder, uterus, or rectum.

To alleviate the pain of childbirth, a pudendal nerve block is performed by injecting a local anesthetic around the pudendal nerve near the ischial spine. To perform the injection, the ischial spine is palpated through the vagina, and the needle is directed toward the ischial spine.

As the head of the baby passes through the vagina during childbirth, the anus and the levator ani muscle are forced posteriorly toward the sacrum and coccyx. The urethra is forced anteriorly toward the pubic symphysis. Perineal lacerations during childbirth are common, and it may be necessary to surgically widen the vaginal orifice (episiotomy). If the perineal body is lacerated, it must be repaired to prevent weakness of the pelvic floor, which could result in prolapse of the urinary bladder, uterus, or rectum.

To alleviate the pain of childbirth, a pudendal nerve block is performed by injecting a local anesthetic around the pudendal nerve near the ischial spine. To perform the injection, the ischial spine is palpated through the vagina, and the needle is directed toward the ischial spine.

Dissection Review

- Replace the muscles of the urogenital triangle in their correct anatomical positions.

- Review the contents of the female superficial perineal pouch. Visit a dissection table with a male cadaver and view the contents of the superficial perineal pouch.

- Use an illustration to review the course of the internal pudendal artery from its origin in the pelvis.

- Use an illustration to review the course and branches of the pudendal nerve.

- Review an illustration showing the urethra and note its course from the urinary bladder to the perineum.

MALE CADAVER

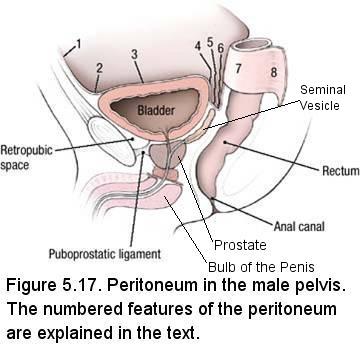

Male Dissection Overview (Tables with Female cadavers are still responsible for this anatomy

The male pelvic cavity contains the urinary bladder anteriorly, male internal genitalia, and the rectum posteriorly (Figure 5.17). The order of dissection will be as follows: The external genitalia will be examined. The peritoneum will be studied in the male pelvic cavity. The pelvis will be sectioned in the midline and the cut surface of the sectioned pelvis will be studied. The ductus deferens will be traced from the anterior abdominal wall to the region between the urinary bladder and rectum. The seminal vesicles and prostate gland will be studied.

Instructions: Peritoneum in the Whole Male Pelvis

- Using Figure 5.17 as a reference, examine the peritoneum in the male pelvis. Note that the peritoneum:

- (1, 2) Passes from the anterior abdominal wall superior to the pubis

- (3) Covers the superior surface of the urinary bladder

- (4) Passes inferiorly along the posterior surface of the urinary bladder

- (5) Has a close relationship to the superior ends of the seminal vesicles

- (6) Passes inferiorly between the urinary bladder and the rectum to form the rectovesical pouch

- (7) Contacts the anterior surface and sides of the rectum

- (8) Forms the sigmoid mesocolon beginning at the level of the third sacral vertebra

- Laterally, a paravesical fossa is apparent on each side of the urinary bladder. Further posteriorly, a pararectal fossa is apparent on each side of the rectum.

Dissection Instructions: Sectioning the Male Pelvis

Both halves of the pelvis will be used to dissect the pelvic viscera, pelvic vasculature, and nerves of the pelvis. One half of the pelvis will be used to demonstrate the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm.

- Begin this dissection with a new scalpel blade.

- Place the cadaver in the supine position.

- In the pelvic cavity make a midline cut, beginning posterior to the pubic symphysis. Carry this midline cut through the superior surface of the urinary bladder. Open the urinary bladder and sponge the interior, if necessary.

- Identify the internal urethral orifice and insert a probe. Use the probe as a guide and continue the midline cut inferior to the urinary bladder, dividing the urethra. Identify the prostate inferior to the urinary bladder. Divide the prostate gland in the midline.

- Extend the midline cut in the posterior direction. Cut through the anterior and posterior

walls of the rectum and the distal part of the sigmoid colon. Sponge them clean.

- The next objective is to sagittally section the penis. Examine the external urethral orifice at the tip of the glans penis (Figure): Push a probe into the external urethral orifice, and then use a scalpel to cut down to the probe from both the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the penis. Cut in the median plane of the penis (it may not be a straight line).

- Advance the probe proximally, and continue to divide the penis. Stop inferior to the pubic symphysis.

- Make a cut in the midline from the pubic symphysis to the coccyx passing through the bulb of the penis (a part of the root of the penis that is located in the midline, deep to the perineal skin) and the anal canal (Figure 5.17).

- Use a saw to make two cuts in the midline (these cuts will occur along the midline from C to D in Figure 5.40):

- Pubic symphysis - Cut through the pubic symphysis from anterior to posterior.

- Sacrum - Turn the cadaver to the prone position. Cut through the sacrum from posterior to anterior. Do not allow the saw to pass between the soft tissue structures that were cut with the scalpel. Spread the opening and extend the midline cut as far superiorly as the body of the third lumbar vertebra.

- Clean the rectum and anal canal.

Dissection Instructions: Spongy Urethra and the Corpora Cavernosa Penis

- Note that the glans penis (L. glans, acorn) is the distal expansion of the corpus spongiosum penis and that it caps the two corpora cavernosa penis. The spongy urethra terminates by passing through the glans.

- Examine the external urethral orifice at the tip of the bisected glans penis.

- Examine the interior of the spongy urethra. Identify the navicular fossa, a widening of the urethra in the glans penis.

- Trace the spongy urethra proximally as it passes within the corpus spongiosum penis, the ventral, unpaired portion of the body of the penis. In the bulb of the penis, the spongy urethra bends at a sharp angle and passes through the perineal membrane (Figure 5.15).

- The openings of the ducts of the bulbourethral glands are in the proximal part of the spongy urethra, but may be too small to see.

- Dorsal to the corpus spongiosum penis, note that the previous cut made to bisect the penis passed between the paired corpora cavernosa penis.

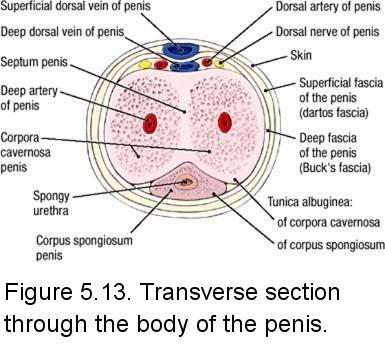

- On the right side of the penis, make a transverse cut through the body of the penis about midway down its length.

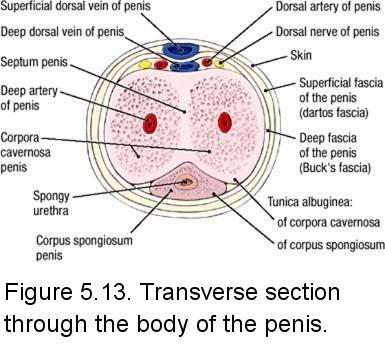

- On the cut surface of the transverse section of the penis, study the relationship of the corpus cavernosum penis and corpus spongiosum penis. Identify (Figure 5.13):

- Tunica albuginea of the corpus cavernosum penis

- Tunica albuginea of the corpus spongiosum penis

- Septum penis

- Study the erectile tissue within the corpus spongiosum penis. Observe that the corpus spongiosum penis surrounds the spongy urethra.

- Study the erectile tissue within the corpus cavernosum penis (Figure 5.13). Identify the

deep artery of the penis near the center of the erectile tissue. Review the origin of the deep artery of the penis from the internal pudendal artery.

Dissection Instructions: Male Internal Genitalia

- Identify the bulb of the penis (Figure 5.15). The bulb of the penis is the unpaired, midline portion of the root of the penis. The bulb of the penis is continuous with the ventral portion of the body of the penis, called the corpus spongiosum (to be examined in more detail in a future lab session). The spongy urethra passes through both the bulb of the penis and the corpus spongiosum en route to the external urethral orifice.

- Identify the perineal membrane. It is located deep to the bulb of the penis and can be identified as a thin line at the deep edge of the bulb (Figure 5.15). Superior (deep) to the perineal membrane, the external urethral sphincter muscle surrounds the membranous urethra. The external urethral sphincter muscle may be difficult to see in the sectioned specimen.

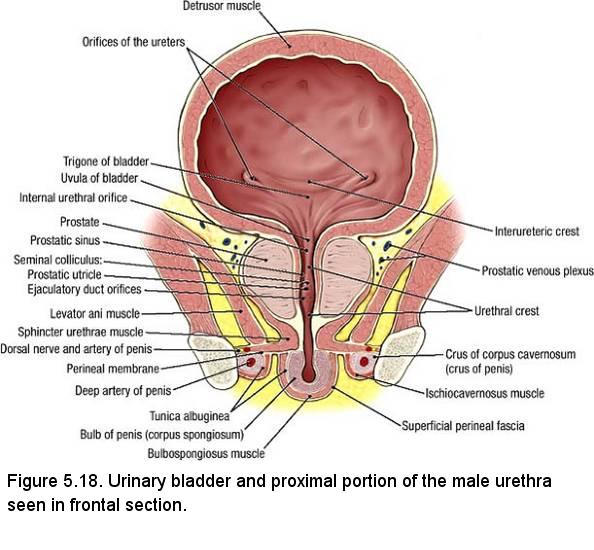

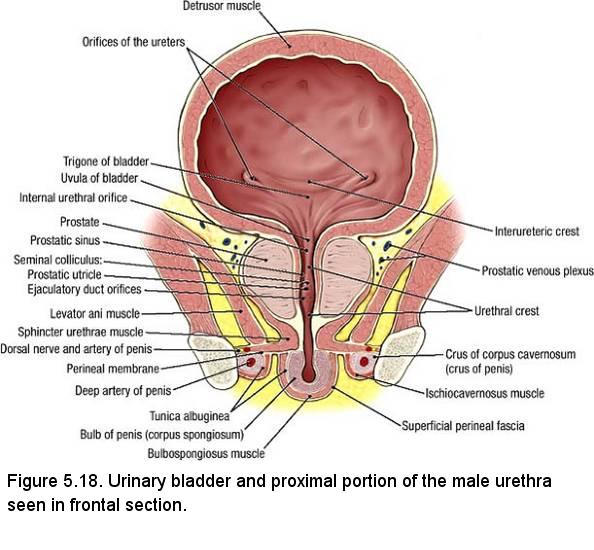

- Examine the interior of the prostatic urethra. The prostatic urethra is about 3 cm

in length and is the part that passes through the prostate. There are a number of structures

that are found on the posterior wall of the prostatic urethra. These structures are really small

and may not be visible if your cuts are off the mark. You do not have to identify them.)

(Figure 5.18):

- Urethral crest - a longitudinal ridge

- Seminal colliculus - an enlargement of the urethral crest

- Prostatic sinus - the groove on either side of the seminal colliculus

- Prostatic utricle - a small opening on the midline of the seminal colliculus

- Opening of the ejaculatory duct - one on either side of the prostatic utricle

- On the sectioned pelvis, trace the path of a drop of urine from the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Identify the three parts of the urethra: prostatic urethra, membranous urethra, and spongy urethra (Figure 5.15).

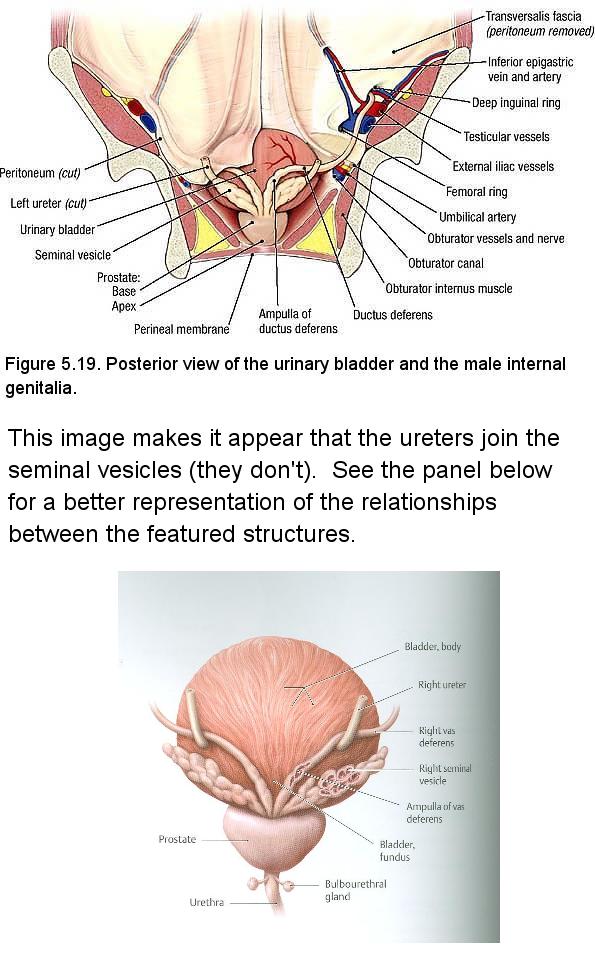

- Find the ductus deferens where it enters the deep inguinal ring lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels (Figure 5.19). Use a probe to break through the peritoneum at the deep inguinal ring. Use blunt dissection to peel the peritoneum off the lateral wall of the pelvis. Strip the peritoneum from lateral to medial, stopping where it comes in contact with the rectum and urinary bladder. Detach the peritoneum and place it in the tissue container.

- Use blunt dissection to trace the ductus deferens from the deep inguinal ring toward the

midline. Observe that the ductus deferens passes superior and then medial to the branches of the

internal iliac artery. Note that the ductus deferens crosses superior to the ureter. - Trace the ductus deferens to the fundus (posterior surface) of the urinary bladder.

- Identify the ampulla of the ductus deferens, which is the enlarged portion just before its termination (Figure 5.19).

- Identify the seminal vesicle. The seminal vesicle is located lateral to the ampulla of the ductus deferens. Use blunt dissection to demonstrate the extent of the seminal vesicle

- Close to the prostate, the duct of the seminal vesicle joins the ductus deferens to form the ejaculatory duct. The ejaculatory duct is delicate and easily torn where it enters the prostate. The ejaculatory duct empties into the prostatic urethra on the seminal colliculus (Figure 5.18).

- Observe the prostate (Figure 5.17). The apex of the prostate is directed inferiorly and the base of the prostate is located superiorly against the neck of the urinary bladder. Use a textbook to study the lobes of the prostate.

Dissection Review

- Review the position of the male pelvic viscera within the lesser pelvis. Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and observe the position of the female pelvic viscera.

- Review the peritoneum in the male pelvic cavity. Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and compare differences in the male and female peritoneum (Figure 5.17 and 5.30).

- Trace the ductus deferens from the epididymis to the ejaculatory duct, recalling its relationships to vessels, nerves, the ureter, and the seminal vesicle.

- Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and trace the round ligament of the uterus from the labium majus to the uterus.

- Compare the pelvic course of the ductus deferens with the pelvic course of the round ligament of the uterus.

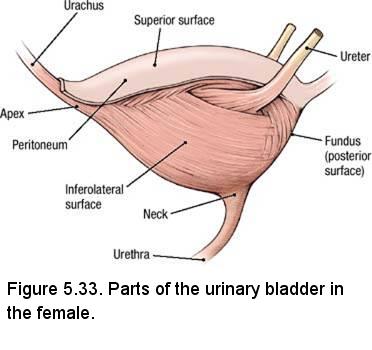

Dissection Overview: Urinary Bladder, Rectum and the Anal Canal in the Male

The order of dissection will be as follows: The parts of the urinary bladder will be studied. The interior of the urinary bladder will be studied. The interior of the rectum and anal canal will be studied.

Dissection Instructions: Urinary Bladder

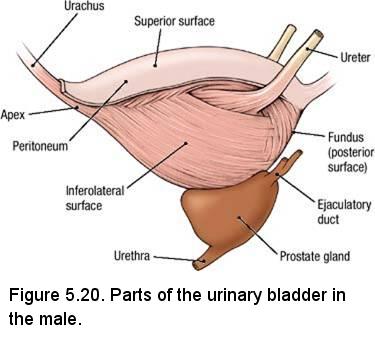

- Identify the parts of the urinary bladder (Figure 5.20):

- Apex - the pointed part directed toward the anterior abdominal wall. The apex of the urinary bladder can be identified by the attachment of the urachus.

- Body - between the apex and fundus.

- Fundus - the inferior part of the posterior wall, also called the base of the urinary bladder. In the male the fundus is related to the ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, and rectum.

- Neck - where the urethra exits the urinary bladder. In the neck of the urinary bladder, the wall thickens to form the internal urethral sphincter, which is an involuntary muscle.

- Apex - the pointed part directed toward the anterior abdominal wall. The apex of the urinary bladder can be identified by the attachment of the urachus.

- Examine the wall of the urinary bladder and note its thickness. The wall of the urinary bladder consists of bundles of smooth muscle called the detrusor muscle (L. detrudere, to thrust out).

- Use the prosected bladder provided to identify the trigone on the inner surface of the fundus (Figure 5.18). The angles of the trigone are the internal urethral orifice and the two orifices of the ureters. The internal urethral orifice is located at the most inferior point in the urinary bladder. NOTE: The trigone of the bladder is derived embryologically from mesoderm (the caudal end of the mesonephric ducts), while the rest of the bladder is endodermally derived. The trigone is more sensitive to stretching than the rest of the bladder. Stretching of the trigone sends signals to the pontine micturition center for bladder emptying.

- Observe that the mucous membrane over the trigone is smooth. The mucous membrane lining the other parts of the urinary bladder lies in folds when the urinary bladder is empty but will accommodate expansion.

- Back at your cadaver, insert the tip of a probe into the orifice of the ureter and observe that the ureter passes through the muscular wall of the urinary bladder in an oblique direction. When the urinary bladder is full (distended), the pressure of the accumulated urine flattens the part of the ureter that is within the wall of the urinary bladder and prevents reflux of urine into the ureter.

- Find the ureter where it crosses the external iliac artery or the bifurcation of the common iliac artery. Use blunt dissection to follow the ureter to the fundus of the urinary bladder.

IN THE CLINIC: Kidney Stones

Kidney stones pass through the ureter to the urinary bladder and they may become lodged in the ureter. The point where the ureter passes through the wall of the urinary bladder is a relatively narrow passage. If a kidney stone becomes lodged, severe colicky pain results. The pain stops suddenly once the stone passes into the bladder.

Kidney stones pass through the ureter to the urinary bladder and they may become lodged in the ureter. The point where the ureter passes through the wall of the urinary bladder is a relatively narrow passage. If a kidney stone becomes lodged, severe colicky pain results. The pain stops suddenly once the stone passes into the bladder.

Dissection Instructions: Rectum and Anal Canal

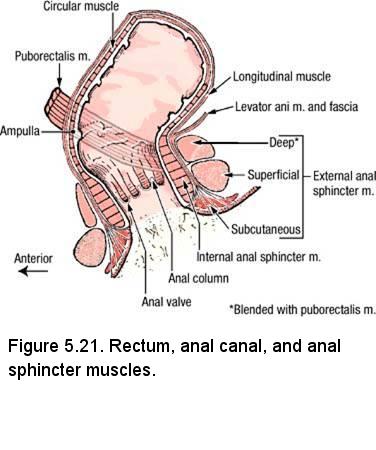

- The rectum begins at the level of the third sacral vertebra. Observe the sectioned pelvis and note that the rectum follows the curvature of the sacrum.

- Identify the ampulla of the rectum (Figure 5.21). At the ampulla, the rectum bends approximately 80° posteriorly (anorectal flexure) and is continuous with the anal canal. Observe that the prostate and seminal vesicles are located close to the anterior wall of the rectum (Figure 5.17).

- Observe that the anal canal is only 2.5 to 3.5 cm in length. The anal canal passes out of the pelvic cavity and enters the anal triangle of the perineum.

- Examine the inner surface of the anal canal (Figure 5.21). The mucosal features of the anal canal may be difficult to identify in older individuals, but attempt to identify the following:

- Anal columns - 5 to 10 longitudinal ridges of mucosa in the proximal part of the anal canal. The anal columns contain branches of the superior rectal artery and vein.

- Anal valves - semilunar folds of mucosa that unite the distal ends of the anal columns. Between the anal valve and the wall of the anal canal is a small pocket called an anal sinus.

- Pectinate (dentate) line - the irregular line formed by all of the anal valves.

- Remind yourself of the existence of anal sphincter muscles that surround the anal canal: the external anal sphincter muscle and the internal anal sphincter (Figure 5.21).

IN THE CLINIC: Rectal Examination

Digital rectal examination is part of the physical examination. The size and consistency of the prostate gland can be assessed by palpation through the anterior wall of the rectum.

Digital rectal examination is part of the physical examination. The size and consistency of the prostate gland can be assessed by palpation through the anterior wall of the rectum.

IN THE CLINIC: Hemorrhoids

In the anal columns, the superior rectal veins of the hepatic portal system anastomose with middle and inferior rectal veins of the inferior vena caval system. An abnormal increase in blood pressure in the hepatic portal system causes engorgement of the veins contained in the anal columns, resulting in internal hemorrhoids. Internal hemorrhoids are covered by mucous membrane and are relatively insensitive to painful stimuli because the mucous membrane is innervated by autonomic nerves. External hemorrhoids are enlargements of the tributaries of the inferior rectal veins. External hemorrhoids are covered by skin and are very sensitive to painful stimuli because they are innervated by somatic nerves (inferior rectal nerves).

In the anal columns, the superior rectal veins of the hepatic portal system anastomose with middle and inferior rectal veins of the inferior vena caval system. An abnormal increase in blood pressure in the hepatic portal system causes engorgement of the veins contained in the anal columns, resulting in internal hemorrhoids. Internal hemorrhoids are covered by mucous membrane and are relatively insensitive to painful stimuli because the mucous membrane is innervated by autonomic nerves. External hemorrhoids are enlargements of the tributaries of the inferior rectal veins. External hemorrhoids are covered by skin and are very sensitive to painful stimuli because they are innervated by somatic nerves (inferior rectal nerves).

Dissection Review

- Use the dissected specimen to review the features of the urinary bladder, rectum, and anal canal.

- Review the relationships of the seminal vesicles, ampulla of the ductus deferens, and ureters to the rectum and fundus of the urinary bladder.

- Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and review the relationships of the uterus, vagina, and ureters to the rectum and fundus of the urinary bladder.

- Review the kidney, the abdominal course of the ureter, the pelvic course of the ureter, and the function of the urinary bladder as a storage organ.

- Review the parts of the male urethra. Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and review the female urethra.

- Review all parts of the large intestine and recall its function in absorption of water and in compaction and elimination of fecal material.

- Recall that the external anal sphincter muscle is composed of skeletal muscle and is under voluntary control, whereas the internal anal sphincter muscle is composed of smooth muscle and is involuntary.

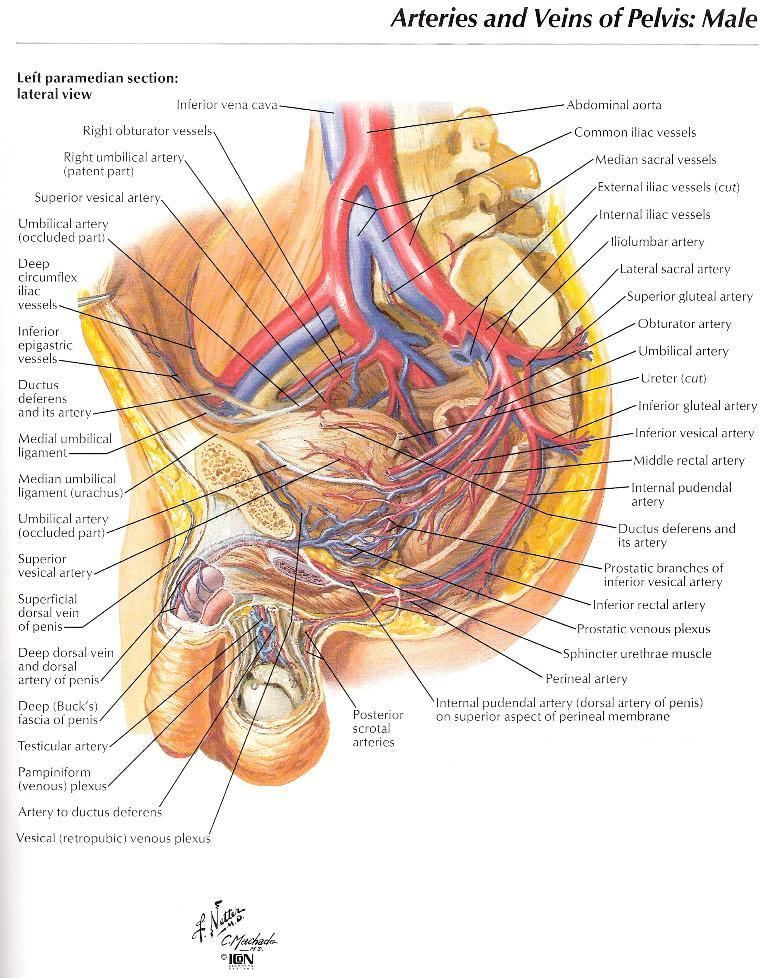

Dissection Overview: Internal Iliac Artery and Sacral Plexus of the Male

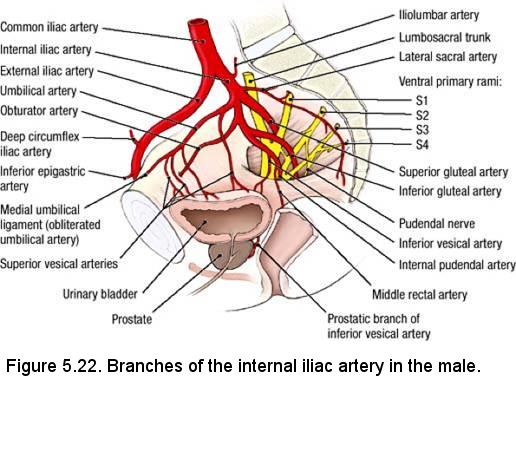

Anterior to the sacroiliac articulation, the common iliac artery divides to form the external and internal iliac

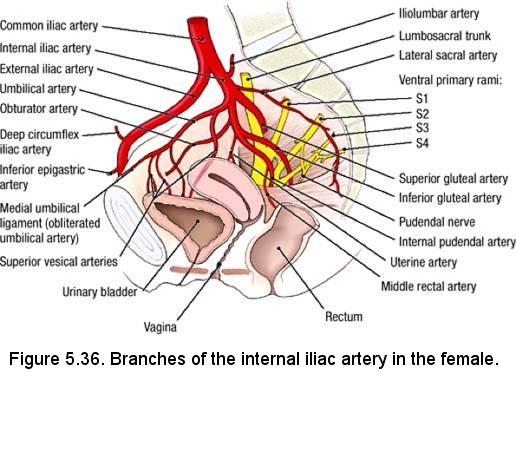

arteries (Figure 5.22). The external iliac artery distributes to the lower limb and the internal iliac artery distributes to the pelvis. The internal iliac artery has the most variable branching pattern of any artery, and it is worth noting at the outset of this dissection that you must use the distribution of the branches to identify them, not their pattern of branching.

The internal iliac artery commonly divides into an anterior division and a posterior division. Branches arising from the anterior division are mainly visceral (branches to the urinary bladder, internal genitalia, external genitalia, rectum, and gluteal region). Branches arising from the posterior division are parietal (branches to the pelvic walls and gluteal region).

The order of dissection will be as follows: The branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery will be identified. The branches of the posterior division of the internal iliac artery will be identified.

Dissection Instructions: Blood Vessels

- The internal iliac vein is typically plexiform. To clear the dissection field, remove all tributaries to the internal iliac vein.

- Identify the common iliac artery and follow it distally until it bifurcates.

- Identify the internal iliac artery. Use blunt dissection to follow the internal iliac artery into the pelvis.

- Identify the branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery (Figure 5.22):

- Umbilical artery - in the medial umbilical fold, find the medial umbilical ligament (the obliterated portion of the umbilical artery) and use blunt dissection to trace it posteriorly to the umbilical artery. Note that several superior vesical arteries arise from the inferior surface of the umbilical artery and descend to the superolateral part of the urinary bladder.

- Obturator artery - passes through the obturator canal. Find the obturator artery where it enters the obturator canal in the lateral wall of the pelvis and follow the artery posteriorly to its origin. In about 20% of cases an aberrant obturator artery (a branch of the external iliac artery) crosses the pelvic brim and is at risk of injury during surgical repair of a femoral hernia.

- Inferior vesical artery - courses toward the fundus of the urinary bladder to supply the urinary bladder, seminal vesicle, and prostate. The inferior vesical artery is a named branch only in the male; in the female it is an unnamed branch of the vaginal artery.

- Middle rectal artery - courses medially toward the rectum. It often arises in common with the inferior vesical artery, making positive identification difficult. Identify the middle rectal artery by tracing it to the rectum. The middle rectal artery, like the inferior vesical artery, sends branches to the seminal vesicle and prostate.

- Internal pudendal artery - exits the pelvic cavity by passing through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. The internal pudendal artery often arises from a common trunk with the inferior gluteal artery.

- Inferior gluteal artery - usually passes out of the pelvic cavity between ventral rami S2 and S3. The inferior gluteal artery exits the pelvis by passing through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. The inferior gluteal artery may share a common trunk with the internal pudendal artery, or less commonly, with the superior gluteal artery.

- Identify the branches of the posterior division of the internal iliac artery (Figure 5.22):

- Iliolumbar artery - passes posteriorly, then ascends between the lumbosacral trunk and the obturator nerve. It may arise from a common trunk with the lateral sacral artery.

- Lateral sacral artery - gives rise to a superior branch and an inferior branch. Observe the inferior branch that passes anterior to the sacral ventral rami.

- Superior gluteal artery - usually exits the pelvic cavity by passing between the lumbosacral trunk and the ventral ramus of S1.

- Use an illustration to study the prostatic venous plexus, vesical venous plexus, and rectal venous plexus. All of these plexuses drain into the internal iliac vein.

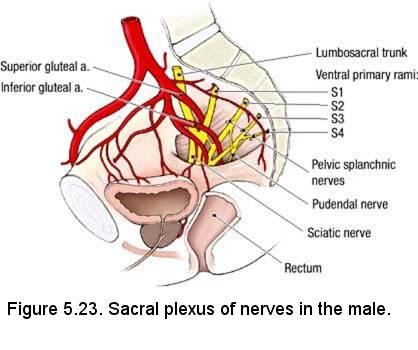

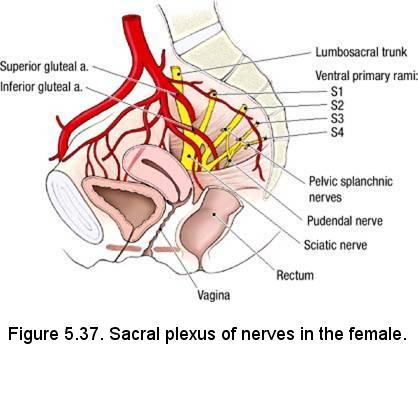

Dissection Instructions: Nerves

The somatic plexuses of the pelvic cavity are the sacral plexus and coccygeal plexus. These plexuses are located between the pelvic viscera and the lateral pelvic wall within the endopelvic fascia. These somatic nerve plexuses are formed by contributions from ventral rami of spinal nerves L4 to S4. The primary visceral nerve plexus of the pelvic cavity is the inferior hypogastric plexus. It is formed by contributions from the hypogastric nerves, sympathetic trunks, and pelvic splanchnic nerves.

- Use your fingers to dissect the rectum from the anterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx.

- Retract the rectum medially and identify the sacral plexus of nerves. The sacral plexus is closely related to the anterior surface

of the piriformis muscle. Verify the following (Figure 5.23):

- The lumbosacral trunk (ventral rami of L4 and L5) joins the sacral plexus.

- The ventral rami of S2 and S3 emerge between the proximal attachments of the piriformis muscle.

- The sciatic nerve is formed by the ventral rami of spinal nerves L4 through S3. The sciatic nerve exits the pelvis by passing through the greater sciatic foramen, usually inferior to the piriformis muscle.

- The superior gluteal artery usually passes between the lumbosacral trunk and the ventral ramus of spinal nerve S1, and exits the pelvis by passing superior to the piriformis muscle.

- The inferior gluteal artery usually passes between the ventral rami of spinal nerves S2 and S3. The inferior gluteal artery exits the pelvis by passing inferior to the piriformis muscle.

- The pudendal nerve receives a contribution from the ventral rami of spinal nerves S2, S3, and S4. The pudendal nerve exits the pelvis by passing inferior to the piriformis muscle.

Below is review of information previously presented. Do not attempt to dissect these structures.

Recall the pelvic splanchnic nerves (nervi erigentes). Pelvic splanchnic nerves are branches of the ventral rami of spinal nerves S2 through S4 (Figure 5.23). Pelvic splanchnic nerves carry preganglionic parasympathetic axons for the innervation of pelvic organs and the distal gastrointestinal tract (from the left colic flexure through the anal canal).

- Recall the sacral portion of the sympathetic trunk is located on the anterior surface of the sacrum, medial to the

ventral sacral foramina.

- Sympathetic trunk - continues from the abdominal region into the pelvis. The sympathetic trunks of the two sides join in the midline near the level of the coccyx to form the ganglion impar.

- Gray rami communicantes - connect the sympathetic ganglia to the sacral ventral rami. Each gray ramus communicans carries postganglionic sympathetic fibers to a ventral ramus for distribution to the lower extremity and perineum.

- Sacral splanchnic nerves - arise from two or three of the sacral sympathetic ganglia and pass directly to the inferior hypogastric plexus (look for the nerve fibers deep to the subperitoneal connective tissue). The inferior hypogastric plexus receives the left and right hypogastric nerves. Sacral splanchnic nerves carry sympathetic fibers that distribute to the pelvic viscera.

IN THE CLINIC: Pelvic Nerve Plexuses

The pelvic splanchnic nerves (parasympathetic outflow of S2, S3, and S4) are closely related to the lateral aspects of the rectum. The inferior hypogastric plexus is located in the connective tissue lateral to the prostate. These autonomic nerve plexuses can be injured during surgery, causing loss of bladder control and erectile dysfunction.Dissection Review

- Review the abdominal aorta and its terminal branches.

- Use the dissected specimen to review the branches of the internal iliac artery. Review the region supplied by each branch.

- Visit a dissection table with a female cadaver and review the arteries that are unique to the female: uterine artery and vaginal artery. Note their relationship to the ureter.

- Review the formation of the sacral plexus and the branches that were dissected in the pelvis.

PELVIC VISCERA AND NEUROVASCULATURE

FEMALE CADAVER

Go to Male

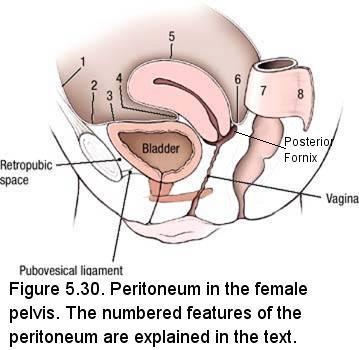

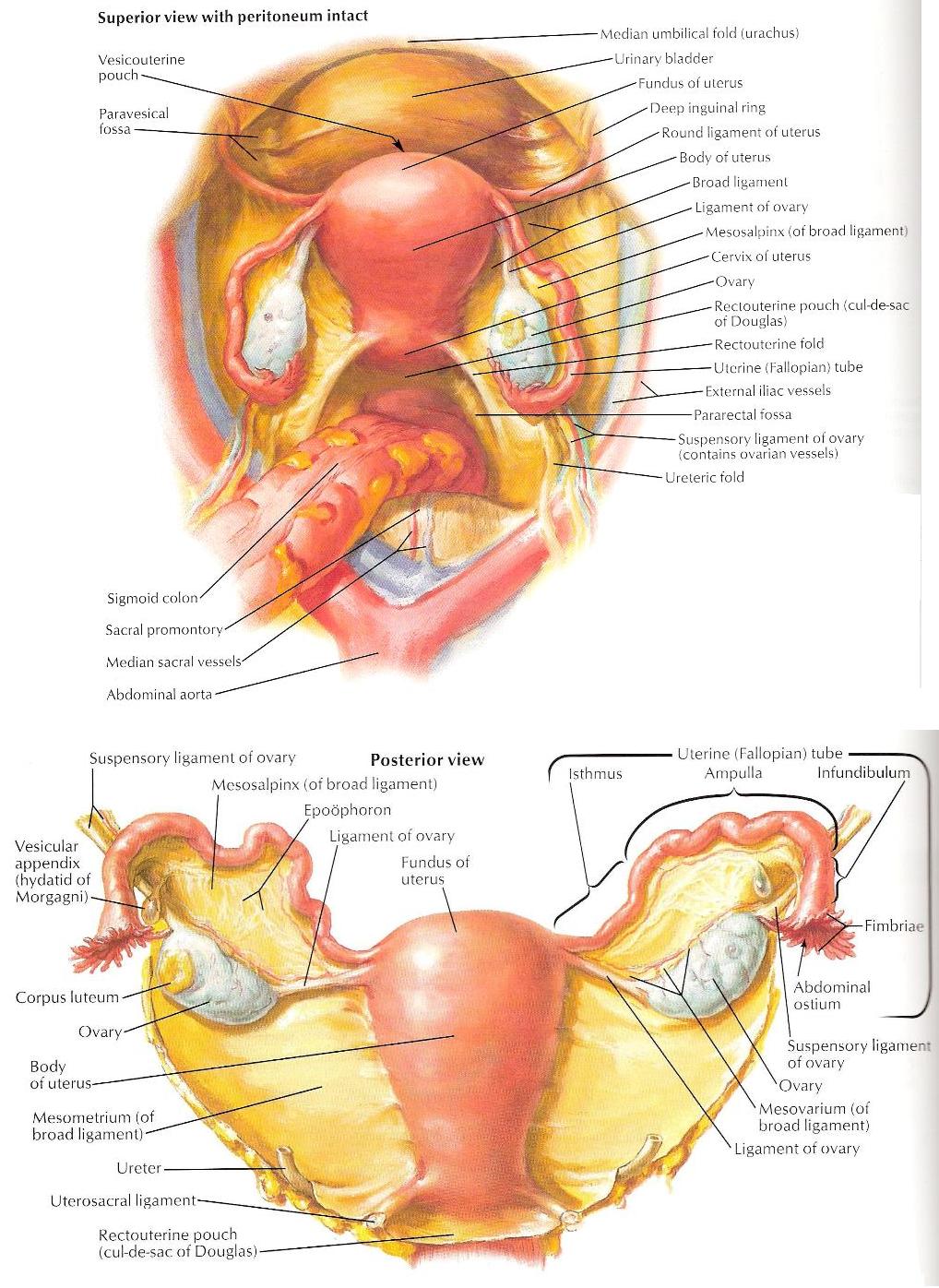

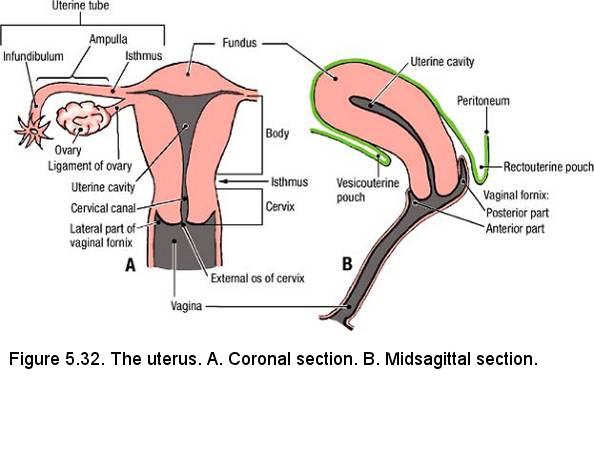

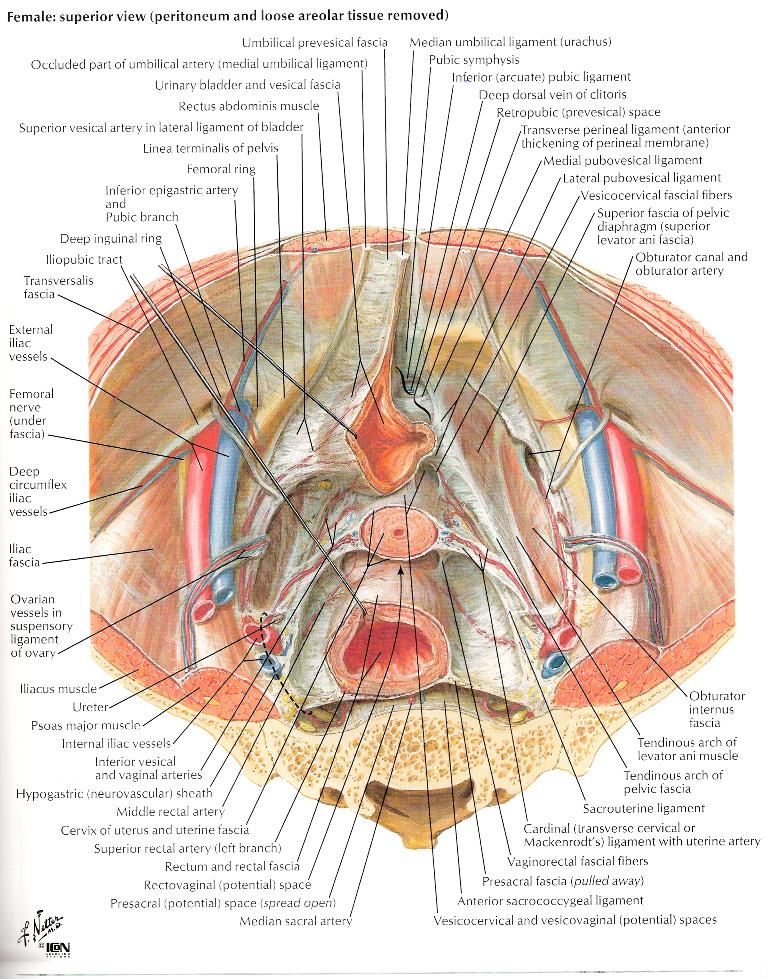

Female Dissection Overview (TABLES WITH MALE CADAVERS ARE STILL RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS ANATOMY)The female pelvic cavity contains the urinary bladder anteriorly, the female internal genitalia, and the rectum posteriorly (Figure 5.30). The term adnexa (L. adnexa, adjacent parts) refers to the ovaries, uterine tubes, and ligaments of the uterus. Removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), with or without the ovaries, is a common surgical procedure. If the uterus has been surgically removed from your cadaver, examine it in other cadavers. The order of dissection will be as follows: The external genitalia of the female will be examined. The peritoneum will be studied in the female pelvic cavity. The pelvis will be sectioned in the midline and the cut surface of the sectioned pelvis will be studied. The uterus and vagina will be studied. The uterine tube will be traced from the uterus to the ovary. The ovary will be studied.

Instructions: Peritoneum in the Whole Female Pelvis

- Using Figure 5.30 as a reference, examine the peritoneum in the female pelvis. Note that the peritoneum:

- (1, 2) Passes from the anterior abdominal wall superior to the pubis

- (3) Covers the superior surface of the urinary bladder

- (4) Passes from the superior surface of the urinary bladder to the uterus where it forms the vesicouterine pouch

- (5) Covers the fundus and body of the uterus and contacts the wall of the posterior part of the vaginal fornix

- (6) Forms the rectouterine pouch (of Douglas) between the uterus and the rectum

- (7) Covers the anterior surface and sides of the rectum

- (8) Forms the sigmoid mesocolon beginning at the level of the third sacral vertebra

- Laterally, a paravesical fossa is apparent on each side of the urinary bladder. Further posteriorly, a pararectal fossa is apparent on each side of the rectum.

- Identify the broad ligament of the uterus. The broad ligament of the uterus is formed by two layers of peritoneum that extend

from the lateral side of the uterus to the lateral pelvic wall. The uterine tube is contained within the superior margin of the

broad ligament of the uterus. The broad ligament of the uterus has three parts (Figure 5.31, lower panel):

- Mesosalpinx (Gr. salpinx, tube) - supports the uterine tube