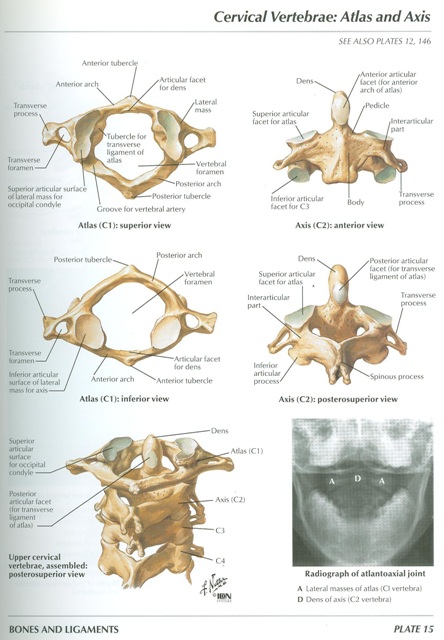

OSTEOLOGY: CERVICAL VERTEBRAE

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this osteology assignment, the student will be able to:

Upon completion of this osteology assignment, the student will be able to:

- Identify major features of the cervical vertebrae

- Distinguish C1 from C2 from C3-C6 from C7 based on these features

The bones of the neck were first studied with the back. Use an articulated skeleton and your atlas to recall several characteristics of the cervical vertebrae. Note that all cervical vertebrae feature:

- Small vertebral bodies (except for C1)

- Relatively large vertebral foramina

- Transverse processes that contain a transverse foramen (foramen transversarium)

Atlas (C1)

- Anterior and posterior arches

- Anterior and posterior tubercles

- Groove for vertebral artery

- Superior articular surface for occipital condyle

- does not have a body

- Vertebral body

- Dens (odontoid process) extending vertically from the body

- Lamina

- Spinous process (note that, like vertebrae C3-C6, it is short and bifid)

- Superior articular facet for atlas

- Vertebral body

- Groove for spinal nerve

- Lamina

- Spinous process (short and bifid)

POSTERIOR TRIANGLE OF THE NECK

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of the assignment relating to the posterior triangles of the neck, the student will be able to:

Upon completion of the assignment relating to the posterior triangles of the neck, the student will be able to:

- Delineate the structural boundaries of the posterior triangle of the neck.

- Describe the fascial arrangements of the neck.

- Identify the superficial and deep structures of the posterior triangle.

- Visualize and relate structures of the neck with respect to adjacent structures.

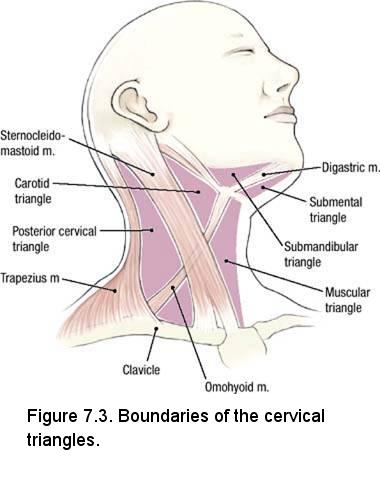

For descriptive purposes the neck is divided into an anterior triangle and a posterior triangle (Fig. 7.3).

You will not dissect the posterior triangle of the neck. This region of the neck will be studied via prosected specimens provided by your instructors. The boundaries of the posterior triangle of the neck are:

- Anterior - the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Posterior - the anterior border of the trapezius muscle

- Inferior - the middle one-third of the clavicle

- Superficial (roof) - superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia

- Deep (floor) - muscles of the neck covered by prevertebral fascia

Instructions (to be performed on the prosected specimen):

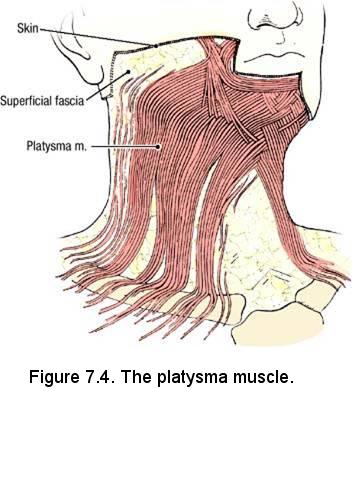

- Examine the platysma muscle (Fig. 7.4). The platysma muscle is invested in the superficial fascia and covers the lower part of the posterior triangle. At its inferior end, the platysma muscle passes superficial to the clavicle and attaches to the superficial fascia of the deltoid and pectoral regions. Superiorly, the platysma muscle is attached to the mandible, skin of the cheek, angle of the mouth, and orbicularis oris muscle. It is innervated by the cervical branch of the facial nerve.

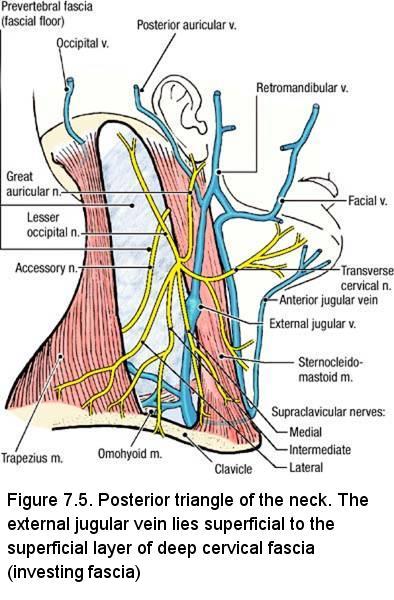

- Identify the external jugular vein (Fig. 7.5). The external jugular vein is in the superficial fascia deep to the platysma muscle. The external jugular vein begins posterior to the angle of the mandible and crosses the superficial surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. About 3 cm superior to the clavicle, the external jugular vein pierces the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (roof of the posterior triangle) to drain into the subclavian vein. Follow the external jugular vein until it passes through the investing layer of deep cervical fascia. Note that these vessels may vary in size considerably from one side to the other, or in different cadavers.

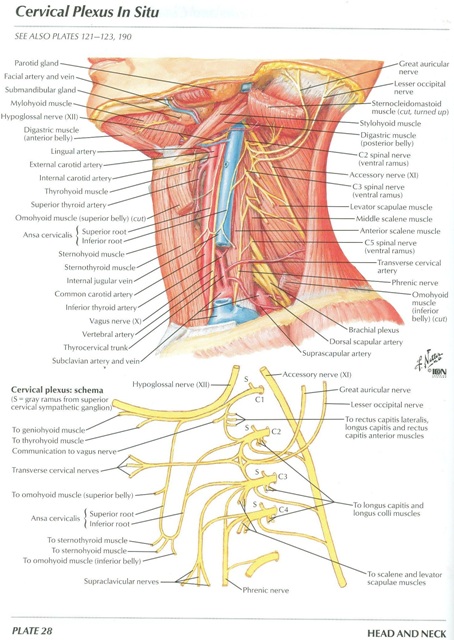

- The skin of the neck and part of the posterior head is innervated by cutaneous nerves that are branches of the cervical plexus. The cutaneous nerves enter the superficial fascia near the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 7.5). Identify:

- Great auricular nerve - crosses the superficial surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle parallel to the external jugular vein. The great auricular nerve supplies the skin of the lower part of the ear and an area of skin extending from the angle of the mandible to the mastoid process.

- Lesser occipital nerve - passes superiorly along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The lesser occipital nerve supplies the part of the scalp that is immediately behind the ear.

- Transverse cervical nerve - passes transversely across the sternocleidomastoid muscle and neck. It supplies the skin of the anterior triangle of the neck.

- Supraclavicular nerves - pass inferiorly to innervate the skin of the shoulder.

- Note that the supraclavicular nerves, the transverse cervical nerve, and the external jugular vein are in contact with the deep surface of the platysma muscle.

- The accessory nerve (Cranial Nerve XI) courses from roughly the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the anterior border of the trapezius muscle (Fig. 7.5). The accessory nerve lies deep to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. The accessory nerve innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the trapezius muscle. Note that branches of spinal nerves C3 and C4 join the accessory nerve in the posterior cervical triangle and these branches provide proprioceptive sensory innervation.

IN THE CLINIC: Diaphragmatic Pain Referred to the Shoulder

The supraclavicular nerves and the phrenic nerve (supplying the diaphragm) share a common origin from spinal cord segments C3 and C4. Irritation of the diaphragmatic parietal pleura (the portion of the serous membrane enveloping the lungs that lies on the diaphragm) or parietal peritoneum covering the diaphragm (e.g., from an enlarged gall bladder) produces pain that is carried by the phrenic nerve and referred to the area supplied by the supraclavicular nerves (shoulder region).

The supraclavicular nerves and the phrenic nerve (supplying the diaphragm) share a common origin from spinal cord segments C3 and C4. Irritation of the diaphragmatic parietal pleura (the portion of the serous membrane enveloping the lungs that lies on the diaphragm) or parietal peritoneum covering the diaphragm (e.g., from an enlarged gall bladder) produces pain that is carried by the phrenic nerve and referred to the area supplied by the supraclavicular nerves (shoulder region).

Review

- The platysma muscle, external jugular vein, and cutaneous nerves of the neck are all located in the superficial fascia. Only the accessory nerve is located deep to the investing layer of deep cervical fascia.

- Use an illustration to review the relationship of the platysma muscle to the cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus. Note that the transverse cervical nerve crosses the neck deep to the platysma muscle but that its branches pass through the muscle to reach the skin of the anterior neck.

- Review the area of distribution of all cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus.

- Review the course of the accessory nerve. Note that the accessory nerve is superficial in the neck where it is vulnerable to injury by laceration or blunt trauma.

ANTERIOR TRIANGLE OF THE NECK

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of the assignment relating to the anterior triangle of the neck, the student will be able to:

Upon completion of the assignment relating to the anterior triangle of the neck, the student will be able to:

- Delineate the structural boundaries of the anterior triangle of the neck.

- Classify the subdivisions of the anterior triangle according to their anatomical boundaries and contents.

- Describe the fascial arrangements of the neck.

- Identify the superficial and deep structures of the anterior triangle.

- Identify the locations of the sympathetic ganglia in the neck.

- Identify the branches of the carotid arteries in the neck.

- Visualize and relate structures of the neck with respect to adjacent structures.

Overview

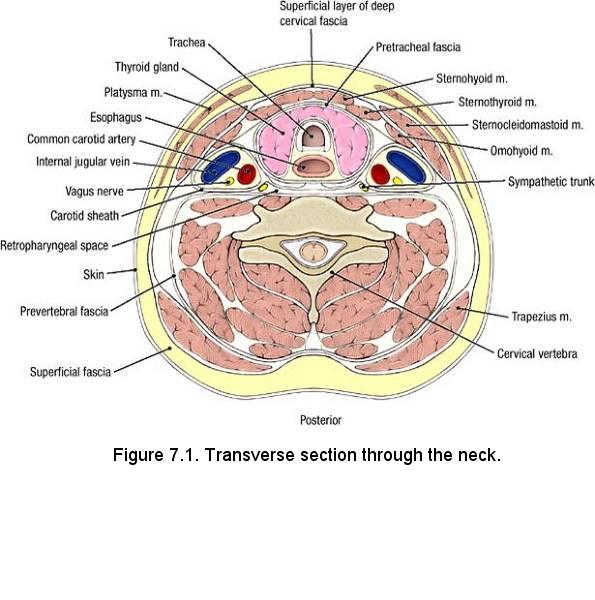

Study a transverse section through the neck (Fig. 7.1). The deep neck contains the cervical vertebral column and

the muscles that move it. The anterior part of the neck houses the cervical viscera. The cervical viscera include:

Study a transverse section through the neck (Fig. 7.1). The deep neck contains the cervical vertebral column and

the muscles that move it. The anterior part of the neck houses the cervical viscera. The cervical viscera include:

- Pharynx and esophagus - the superior parts of the digestive tract

- Larynx and trachea - the superior parts of the respiratory tract

- Thyroid gland and parathyroid glands

- Posterior - the cervical vertebrae

- Posterolateral - the scalene muscles (not labeled in Fig. 7.1)

- Lateral - the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Anterior - the infrahyoid muscles

The boundaries of the anterior triangle of the neck are (Fig. 7.3):

- Anterior - the median line of the neck

- Posterior - the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Superior - the inferior border of the mandible

- Superficial (roof) - superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia

- Deep (floor) - prevertebral fascia

- Hyoid bone - (Gr. hyoideus, U-shaped) at the angle between the floor of the mouth and the superior end of the neck

- Thyrohyoid membrane - stretching between the thyroid cartilage and hyoid bone

- Thyroid cartilage - (Gr. thyreoeides, shield) in the anterior midline of the neck

Dissection Instructions: Superficial Fascia

- The skin is thin on the neck. Be careful when removing it; remove only the skin, leaving as much subcutaneous tissue as possible.

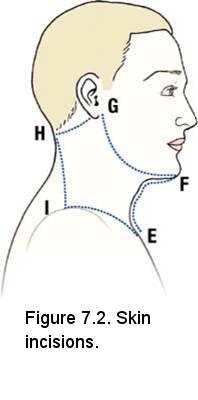

- Refer to Fig. 7.2 and make an anterior midline skin incision from the jugular notch of the sternum (E) to the chin (F).

- Make a second skin incision along the margin of the mandible from point F to just below the ear lobe (G). If the face has been dissected, part of this incision has been made previously.

- Make a skin incision in the transverse plane from point G to the external occipital protuberance (H). If the back has been dissected, part of this incision has been made previously.

- If the back has not been dissected, make a skin incision along the anterior border of the trapezius muscle from point H to the acromion (I).

- If the thorax has not been dissected, make an incision along the anterior surface of the clavicle from point I to the jugular notch of the sternum (E).

- Beginning at the anterior midline, reflect the skin in the lateral direction as far as the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. Detach the skin.

- Near the clavicle, use a probe to raise the inferior border of the platysma muscle. Carefully use blunt dissection to free the platysma muscle from the vessels and nerves on its deep surface and reflect the muscle superiorly as far as the mandible. Leave the platysma muscle attached along the border of the mandible. This muscle is very thin and fragile.

- Follow the external jugular vein superiorly and observe that it is formed by the joining of the posterior division of the retromandibular vein and the posterior auricular vein (Fig. 7.5).

- In the superficial fascia near the anterior midline, note the anterior jugular vein (Fig. 7.5). It courses inferiorly near the midline to the suprasternal region where it penetrates the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. The anterior jugular vein passes deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle to join the external jugular vein in the root of the neck. Remember that superficial veins are variable and inconsistent; therefore these vessels may not be readily apparent.

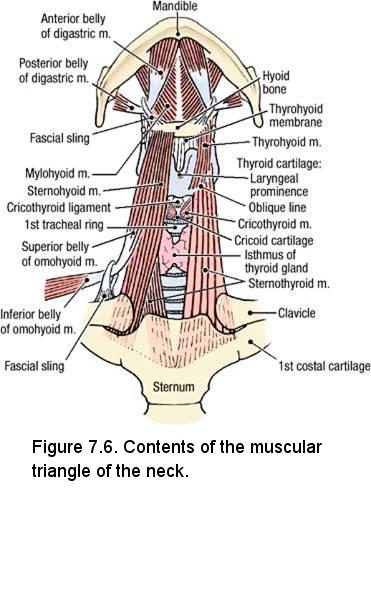

Dissection Instructions: Muscular Triangle

The contents of the muscular triangle of the neck are the infrahyoid muscles, the thyroid gland, and the parathyroid glands. The boundaries

of the muscular triangle are (Fig. 7.3):

- Superolateral - superior belly of the omohyoid muscle

- Inferolateral - anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Medial - median plane of the neck

- In the midline of the neck, use a probe to break through the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia and identify the sternohyoid muscle (Fig. 7.6). The inferior attachment of the sternohyoid muscle is the sternum and its superior attachment is the body of the hyoid bone. The sternohyoid muscle depresses the hyoid bone.

- Lateral to the sternohyoid muscle, identify the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle. The superior belly is attached to the inferior border of the hyoid bone. The inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle attaches to the superior border of the scapula near the suprascapular notch. The omohyoid muscle depresses the hyoid bone.

- Use blunt dissection to loosen the medial border of the sternohyoid muscle from the structures that lie deep to it. Use scissors to transect the sternohyoid muscle close to the hyoid bone and reflect the muscle inferiorly.

- Use a probe to raise the medial border of the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle and loosen it from deeper structures. Use scissors to transect the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle close to the hyoid bone and reflect it inferiorly. Repeat this bilaterally.

- Identify the sternothyroid muscle (Fig. 7.6). The inferior attachment of the sternothyroid muscle is the sternum and its superior attachment is the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage. The sternothyroid muscle depresses the larynx.

- Identify the thyrohyoid muscle. The inferior attachment of the thyrohyoid muscle is the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage and its superior attachment is the hyoid bone. The thyrohyoid muscle elevates the larynx.

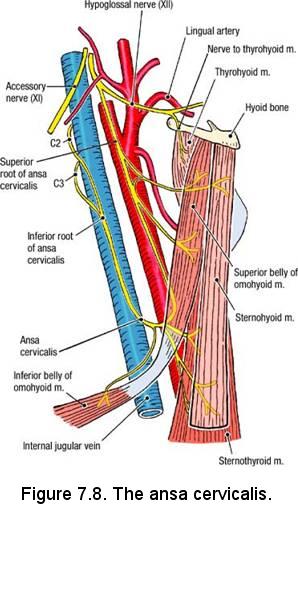

- The ansa cervicalis innervates three of the four infrahyoid muscles: the sternohyoid, omohyoid, and sternothryoid muscles. It will be identified later.

- Gently retract the right and left sternothyroid muscles to widen the gap in the midline. Identify (Fig. 7.6):

- Laryngeal prominence

- Cricothyroid ligament

- Cricoid cartilage

- First tracheal ring

- Isthmus of the thyroid gland

IN THE CLINIC: Tracheotomy (tracheostomy) is the creation of an opening into the trachea. As an emergency operation, it must be rapidly

performed in cases with sudden obstruction of the airway (e.g., aspiration of a foreign body, edema of the larynx, or paralysis of the

vocal folds). The opening is made in the midline between the infrahyoid muscles of the neck.

Dissection Instructions: Submandibular Triangle

- The contents of the submandibular triangle are the submandibular gland, facial artery, facial vein, stylohyoid

muscle, part of the hypoglossal nerve (Cranial Nerve XII), and lymph nodes. The boundaries of the submandibular triangle are

- Superior - inferior border of the mandible

- Anteroinferior - anterior belly of the digastric muscle

- Posteroinferior - posterior belly of the digastric muscle

- Superficial (roof) - superficial layer of deep cervical fascia

- Deep (floor) - mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus muscle

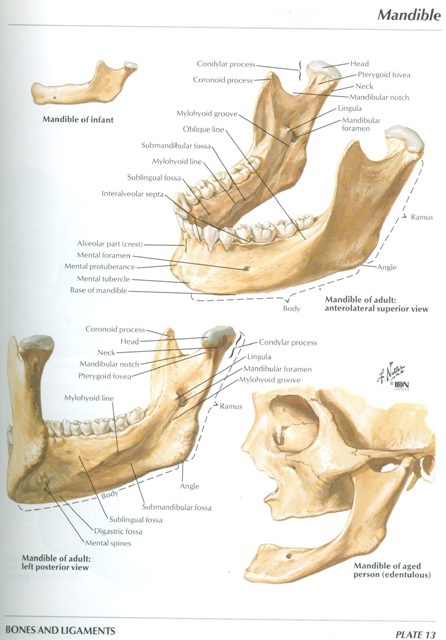

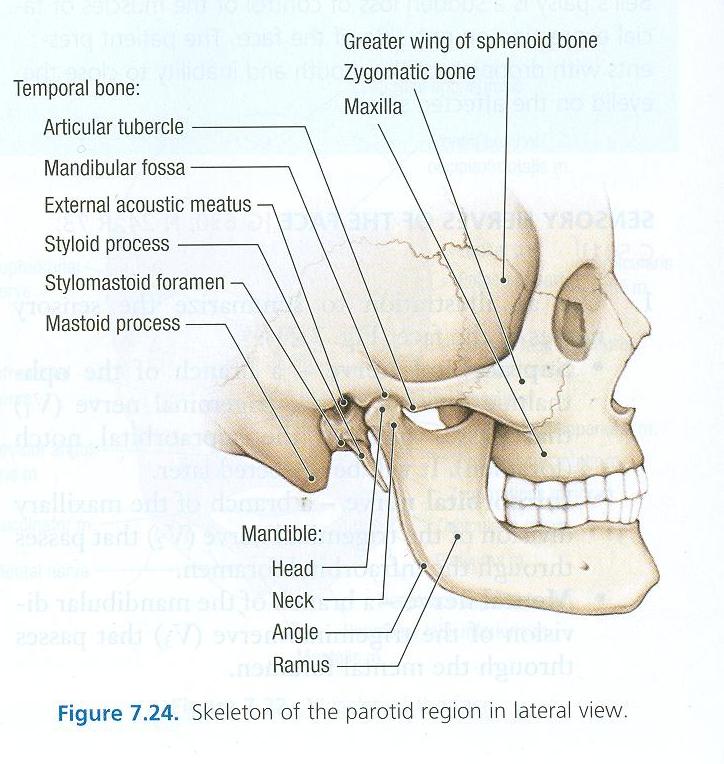

- Refer to a skull. On the temporal bone, identify the mastoid process and the styloid process.

- Examine the inner aspect of the mandible (See Netter, Plate 13) and identify:

- Digastric fossa

- Mylohyoid line

- Submandibular fossa

- Mylohyoid groove

- On the cadaver, identify the submandibular gland and use a probe to define its borders (See Netter, Plate 28). Note that a portion of the gland extends deep to the posterior border of mylohyoid muscle.

- Use blunt dissection to separate the facial artery and facial vein from the submandibular gland. Note that the facial vein passes superficial to the submandibular gland and the facial artery courses deep to the gland.

- Preserve the facial vessels and use scissors to remove the superficial part of the submandibular gland. Do not disturb the deep part of the gland.

- Use blunt dissection to clean the superficial surface of the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle (Fig. 7.6). The anterior attachment of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle is the digastric fossa of the mandible. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V3). The posterior attachment of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is the mastoid process of the temporal bone and it is innervated by the facial nerve (Cranial Nerve VII). The two bellies attach to each other by the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle. The intermediate tendon is attached to the body and the greater horn of the hyoid bone by a fibrous sling. The digastric muscle elevates the hyoid bone and depresses the mandible.

- Identify the tendon of the stylohyoid muscle, which attaches to the body of the hyoid bone by straddling the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle. The stylohyoid muscle is innervated by the facial nerve and it elevates the hyoid bone.

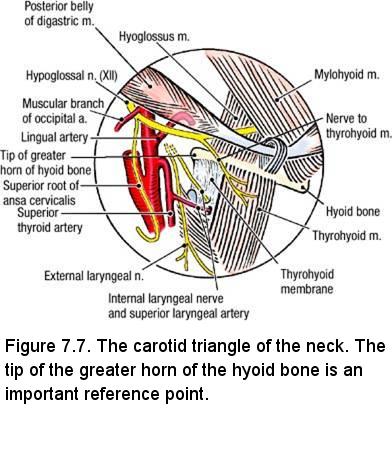

- Use a probe to follow the hypoglossal nerve (Cranial Nerve XII) through the submandibular triangle. Observe that the hypoglossal nerve enters the submandibular triangle by passing deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. It passes deep to the mylohyoid muscle within the submandibular triangle (Fig. 7.7).

Dissection Instructions: Submental Triangle

The contents of the submental triangle are the submental lymph nodes. The submental triangle is an unpaired triangle that crosses the midline.

The boundaries of the submental triangle are (Fig. 7.3):

- Right and left - anterior bellies of the right and left digastric muscles

- Inferior - hyoid bone

- Superficial (roof) - superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia

- Deep (floor) - mylohyoid muscle

Dissection Instructions: Carotid Triangle

The contents of the carotid triangle are the common, internal, and external carotid arteries, the branches of the external carotid

artery, part of the hypoglossal nerve, and branches of the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X). The boundaries of the carotid triangle

are (Fig. 7.3):

- Inferomedial - superior belly of the omohyoid muscle

- Inferolateral - anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Superior - posterior belly of the digastric muscle

- Clean the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle from its inferior end to its superior attachment. Use blunt dissection to free the anterior border of the muscle from the deep cervical fascia.

- Transect the sternocleidomastoid muscle about 5 cm superior to its attachments to the sternum and clavicle. You may need to alternate between freeing the muscle from the underlying deep cervical fascia and continuing the transection a little at a time.

- Reflect the sternocleidomastoid muscle superiorly. Use your fingers to free the sternocleidomastoid muscle from the deep cervical fascia as far superiorly as the mastoid process. Release of the sternocleidomastoid muscle up to the mastoid process is important to facilitate disarticulation of the head in a later dissection.

- Find the accessory nerve (Cranial Nerve XI) where it crosses the deep surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle near the base of the skull (See Netter, Plate 28). Trace the accessory nerve superiorly as far as possible. Note that the accessory nerve passes through the jugular foramen to exit the skull but this relationship is too far superior to be seen at this time.

- To allow better access to deeper structures cut the common facial vein where it empties into the internal jugular vein. Only if necessary, transect the digastric muscle at its intermediate tendon and reflect the posterior belly.

- Palpate the tip of the greater horn of the hyoid bone (Figure 7.7) and 7.8). Find the hypoglossal nerve superior to the tip of the greater horn of the hyoid bone. Observe that a muscular branch of the occipital artery crosses superior to the hypoglossal nerve. The hypoglossal nerve carries axons of spinal nerve C1 that branch off as the nerve to the thyrohyoid muscle.

- Use blunt dissection to trace the hypoglossal nerve anteriorly. Verify that the hypoglossal nerve passes medial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and deep to the mylohyoid muscle (Figure 7.7). The hypoglossal nerves passes superficial to the hyoglossus muscle

- The superior root of the ansa cervicalis travels with the hypoglossal nerve (Fig. 7.8). The superior root of the ansa cervicalis is mainly composed of fibers from C1. The inferior root of the ansa cervicalis (C2, C3) passes around the carotid sheath to join the superior root. Thus, a loop (L. ansa, handle) is formed.

- Clean the ansa cervicalis and trace its delicate branches to the lateral borders of the three infrahyoid muscles (Fig. 7.8) that it supplies: the sternohyoid, omohyoid, and sternothyroid muscles. These three infrahyoid muscles are often referred to as the SOS muscles (after the first letters of their names).

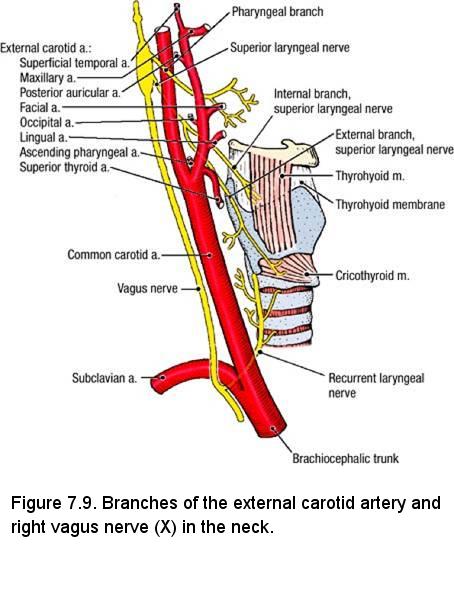

- Use a probe to gently raise the posterior border of the thyrohyoid muscle and identify the thyrohyoid membrane that extends between the thyroid cartilage and the hyoid bone (Fig. 7.9). Find the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve where it passes through the thyrohyoid membrane. The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve supplies sensory fibers to the mucosa of the larynx.

- Follow the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve proximally. It joins the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve to form the superior laryngeal nerve (Fig. 7.9). The superior laryngeal nerve may be too far superior to be seen at this stage of the dissection.

- Trace the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve distally and observe that it innervates the cricothyroid muscle. It also innervates part of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle.

- While preserving the ansa cervicalis, use scissors to open the carotid sheath. The carotid sheath contains the common carotid artery, internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X).

- Observe that the internal jugular vein is located lateral to the common carotid or internal carotid artery in the carotid sheath. Use an illustration to study its largest tributaries: common facial vein, superior thyroid vein, and middle thyroid vein. Use blunt dissection to separate the internal jugular vein from the common and internal carotid arteries.

- At the level of the superior border of the thyroid cartilage, find the origin of the external carotid artery (Fig. 7.9). Use blunt dissection to follow the external carotid artery superiorly until it passes on the medial side of (deep to) the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Temporarily replace the posterior belly of the digastric muscle in its correct anatomical position to confirm this relationship.

- The external carotid artery has six branches in the carotid triangle (Fig. 7.9). Each branch has a companion vein that may be removed to clear the dissection field. At this time, identify the four bolded branches:

- Superior thyroid artery - arises from the anterior surface of the external carotid artery at the level of the superior horn of the thyroid cartilage. The superior thyroid artery descends to the superior pole of the lobe of the thyroid gland. The superior laryngeal artery is a branch of the superior thyroid artery, which pierces the thyrohyoid membrane together with the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

- Lingual artery - arises from the anterior surface of the external carotid artery at the level of the greater horn of the hyoid bone (Fig. 7.9). It passes deeply into the muscles of the tongue.

- Facial artery - arises from the anterior surface of the external carotid artery immediately superior to the lingual artery (Fig. 7.9). The facial artery crosses the inferior border of the mandible to enter the face. In 20% of cases, the lingual and facial arteries arise from a common trunk.

- Occipital artery - arises from the posterior surface of the external carotid artery and supplies part of the scalp (Fig. 7.9).

- Posterior auricular artery - arises from the posterior surface of the external carotid artery and passes posterior to the ear to supply part of the scalp. Do not look for the posterior auricular artery.

- Ascending pharyngeal artery - the sixth branch of the external carotid artery. It branches from the medial surface of the external carotid artery. Do not look for the ascending pharyngeal artery.

- At the bifurcation of the common carotid artery is the carotid sinus, a dilation of the origin of the internal carotid artery. The wall of the carotid sinus contains pressoreceptors that monitor blood pressure. The carotid sinus is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (Cranial Nerve IX) and the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X).

- The carotid body is a small mass of tissue located on the medial aspect of the carotid bifurcation. The carotid body monitors changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide concentration of the blood. The carotid body is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (Cranial Nerve IX) and the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X). Do not look for the carotid body.

- Identify the internal carotid artery and note that it has no branches in the neck.

- Identify the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) within the carotid sheath where it lies between and posterior to the vessels (Fig. 7.9). To see the vagus nerve, retract the internal jugular vein laterally and the common carotid artery medially.

Dissection Review

- Replace the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the infrahyoid muscles in their correct anatomical positions. Review the attachments and actions of the infrahyoid muscles.

- Review the cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus. Review the ansa cervicalis.

- Use the dissected specimen to review the positions of the common carotid and internal carotid arteries, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve within the carotid sheath.

- Follow each branch of the external carotid artery through the regions dissected, noting their relationships to muscles, nerves, and glands.

- Trace the branches of the superior laryngeal nerve distally and note their distribution.

- Review the course of the hypoglossal nerve.

- Review the ansa cervicalis and its relationship to the hypoglossal nerve and carotid sheath.

- Note that the superior laryngeal nerve passes medial to the internal and external carotid arteries and the hypoglossal nerve passes lateral to the internal and external carotid arteries.

ROOT OF THE NECK

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of the assignments relating to the root of the neck, the student will be able to:

Upon completion of the assignments relating to the root of the neck, the student will be able to:

- Delineate the structural boundaries of the root of the neck.

- Describe the fascial arrangements of the neck.

- Identify the structures found in the root of the neck.

- Identify the branches of the subclavian artery.

- Visualize and relate structures of the neck with respect to adjacent structures.

The order of dissection will be as follows: The thyroid glands will be studied. The branches of the subclavian artery will be dissected. The course of the vagus and phrenic nerves will be studied. Some of these structures will be followed superiorly or inferiorly beyond the root of the neck.

Dissection Instructions: Thyroid Glands

The cervical viscera are the pharynx, esophagus, larynx, trachea, thyroid gland, and parathyroid glands. The thyroid gland and parathyroid

glands lie between the infrahyoid muscles and the larynx and trachea, and these glands will be dissected now. The pharynx, esophagus, larynx,

and trachea will be dissected after head disarticulation has been performed.

- Once again, reflect the sternocleidomastoid and sternohyoid muscles inferiorly. Reflect the sternothyroid muscle by cutting the muscle along its attachment to the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage.

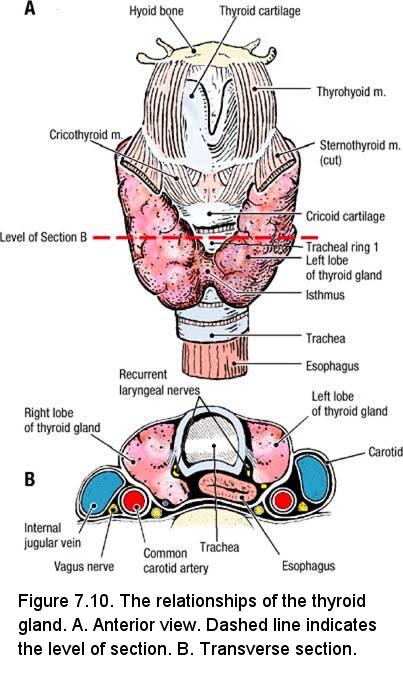

- Observe the thyroid gland. The thyroid gland is located at vertebral levels C5 to T1. Laterally, the thyroid gland is in contact with the carotid sheath (Fig. 7.10B).

- Identify the right lobe and left lobe of the thyroid gland. The two lobes are connected by the isthmus of the thyroid gland, which crosses the anterior surface of tracheal rings 2 and 3 (Fig. 7.10A).

- Frequently, the thyroid gland has a pyramidal lobe that extends superiorly from the isthmus. The pyramidal lobe is a remnant of embryonic development that shows the route of descent of the thyroid gland.

- Identify the superior thyroid artery where it enters the superior end of the lobe of the thyroid gland. Recall that the superior thyroid artery is a branch of the external carotid artery. The inferior thyroid artery will be dissected later.

- The superior and middle thyroid veins are tributaries to the internal jugular vein. The right and left inferior thyroid veins descend into the thorax on the anterior surface of the trachea. The right and left inferior thyroid veins drain into the right and left brachiocephalic veins, respectively. You need not preserve the thyroid veins.

- The thyroidea ima artery is a relatively rare (published reports place the incidence at 2% to 12% of the population) but clinically significant variant. When present, the thyroidea ima artery enters the thyroid gland from inferiorly, near the midline.

- Use scissors to cut the isthmus of the thyroid gland. Use blunt dissection to detach the capsule of the thyroid gland from the tracheal rings. Spread the lobes widely apart.

- On both sides of the cadaver, use blunt dissection to display the recurrent laryngeal nerve that passes immediately posterior to the lobe of the thyroid gland in the groove between the trachea and esophagus. Use an illustration to note the close relationship of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the thyroid gland (Fig. 7.10B).

- On the posterior aspect of the lobes of the thyroid gland are the parathyroid glands. The parathyroid glands are about 5 mm in diameter and may be darker in color than the thyroid gland. Usually, there are two parathyroid glands on each side of the neck but the number can vary from one to three. Do not look for the parathyroid glands.

IN THE CLINIC: Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

If a recurrent laryngeal nerve is injured by a thyroid tumor or during thyroidectomy (removal of the thyroid gland), paralysis of the laryngeal muscles will occur on the affected side. The result is hoarseness of the voice.

If a recurrent laryngeal nerve is injured by a thyroid tumor or during thyroidectomy (removal of the thyroid gland), paralysis of the laryngeal muscles will occur on the affected side. The result is hoarseness of the voice.

IN THE CLINIC: Parathyroid Glands

The parathyroid glands play an important role in the regulation of calcium metabolism. During thyroidectomy, these small endocrine glands are in danger of being damaged or removed. To maintain proper serum calcium levels, at least one parathyroid gland must be retained during surgery.

The parathyroid glands play an important role in the regulation of calcium metabolism. During thyroidectomy, these small endocrine glands are in danger of being damaged or removed. To maintain proper serum calcium levels, at least one parathyroid gland must be retained during surgery.

Dissection Instructions: Subclavian Artery

The root (base) of the neck is the junction between the thorax and the neck. The root of the neck is an important area because it lies

superior to the superior thoracic aperture. All structures that pass between the head and thorax or the upper limb and thorax must pass

through the root of the neck.

- Use a stryker saw to make a cut through each of the sternoclavicular joints, detaching the clavicle from the manubrium of the sternum. This cut will permit the clavicles to be partially reflected inferiorly about one inch, allowing greater access to the root of the neck. Do not displace the clavicle downward by more than an inch. Take care to not damage the pectoral muscles.

- Reflect the sternocleidomastoid, sternohyoid muscle, and sternothyroid muscles inferiorly.

- Clean the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle. Note that its inferior belly and superior belly are joined by an intermediate tendon. Review its attachments and action.

- Use scissors to cut the fascial sling that binds the intermediate tendon of the omohyoid muscle to the clavicle.

- Follow the external jugular vein through the investing layer of deep cervical fascia. Note that the external jugular vein is the only tributary of the subclavian vein. To expose the blood vessels in the root of the neck, remove the investing layer of deep cervical fascia that forms the roof of the lower part of the posterior cervical triangle.

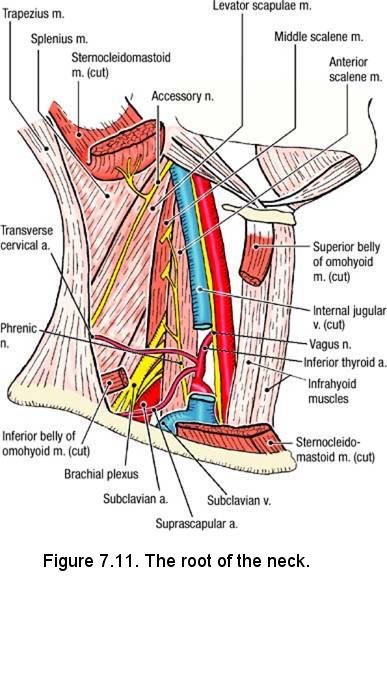

- Identify the subclavian vein (Fig. 7.11). Use blunt dissection to loosen the subclavian vein from structures that lie deep to it. The subclavian vein lies anterior to the anterior scalene muscle.

- Follow the subclavian vein medially to the point where it is joined by the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic vein. On the left side only, cut the internal jugular vein where it joins the subclavian vein.

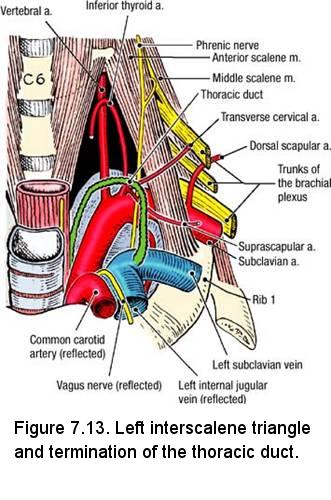

- The thoracic duct is formed in the abdomen by the union of smaller lymphatic ducts, notably the cisterna chyli, and ascends through the posterior mediastinum (posterior region of the thorax), to join with the venous systems in the root of the neck at the junction of the left subclavian vein and left internal jugular vein. You will see most of the thoracic duct when you dissect the thorax. Here, lift the sectioned left internal jugular vein, and find the thoracic duct as it arches anteriorly and to the left to join the venous system near the junction of the left subclavian vein and the left internal jugular vein (Fig. 7.13). The thoracic duct is usually a single structure, which has the diameter of a small vein, but it may be represented by several smaller ducts.

- On the right side of the neck, several small lymphatic vessels join with lymph vessels from the right upper limb and right side of the thorax to form the right lymphatic duct. The right lymphatic duct drains into the junction of the right subclavian and right internal jugular veins. Do not look for the right lymphatic duct.

- Cut the subclavian vein just lateral to the entrance of the external jugular vein, and reflect the subclavian vein medially. Identify the subclavian artery. Look at an atlas figure and observe that the right subclavian artery is a branch of the brachiocephalic trunk and the left subclavian artery is a branch of the aortic arch. The subclavian artery lies between the anterior and middle scalene muscles together with the supraclavicular part of the brachial plexus.

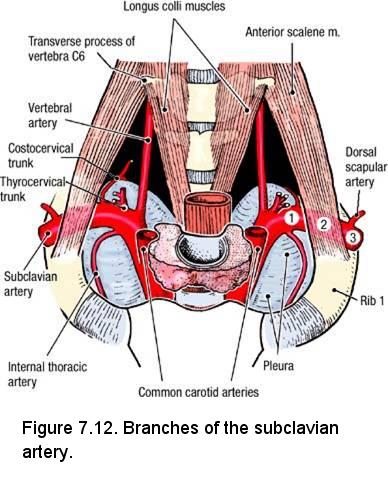

- The subclavian artery has three parts that are defined by its relationship to the anterior scalene muscle (Fig. 7.12):

- First part - from its origin to the medial border of the anterior scalene muscle

- Second part - posterior to the anterior scalene muscle

- Third part - between the lateral border of the anterior scalene muscle and the lateral border of the first rib

- The first part of the subclavian artery has three branches:

- Internal thoracic artery - arises from the anteroinferior surface of the subclavian artery and passes inferiorly to supply the anterior thoracic wall (Fig. 7.12).

- Thyrocervical trunk - arises from the anterosuperior surface of the subclavian artery (Fig. 7.12). The thyrocervical trunk has three branches:

- Transverse cervical artery - crosses the root of the neck about 2 to 3 cm superior to the clavicle and deep to the omohyoid muscle (Fig. 7.13). It supplies the trapezius muscle. NOTE: The superficial branch of the transverse cervical artery enters the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. The deep branch of the transverse cervical artery runs along the rhomboid muscles and is called the dorsal scapular artery. The dorsal scapular artery can also arise as a separate artery from the subclavian artery (usually from the third part).

- Suprascapular artery - passes laterally and posteriorly to the region of the suprascapular notch (Fig. 7.13). It passes superior to the transverse scapular ligament and supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

- Inferior thyroid artery - passes medially toward the thyroid gland. Trace the inferior thyroid artery toward the thyroid gland. Usually, the inferior thyroid artery passes posterior to the cervical sympathetic trunk. The ascending cervical artery is a branch of the inferior thyroid artery.

- Note that the transverse cervical and suprascapular arteries may arise via a common trunk from the thyrocervical trunk or they may arise directly from the subclavian artery.

- Vertebral artery - courses superiorly between the anterior scalene muscle and the longus colli muscle (Fig. 7.12). The vertebral artery passes superiorly into the transverse foramen of vertebra C6.

- The second part of the subclavian artery has one branch, the costocervical trunk (Fig. 7.12). The costocervical trunk divides into the deep cervical artery and the supreme intercostal. The supreme intercostal artery gives rise to posterior intercostal arteries 1 and 2. You do not need to find the costocervical trunk.

- The third part of the subclavian artery has one branch, the dorsal scapular artery. The dorsal scapular artery passes between the superior and middle trunks of the supraclavicular part of the brachial plexus to supply the muscles of the scapular region (Fig. 7.13). In about 30% of cases the dorsal scapular artery arises from the transverse cervical artery instead of from the subclavian artery.

- On both sides of the neck, find the vagus nerves in their respective carotid sheaths.

- Trace the right vagus nerve to where it passes anterior to the subclavian artery, where it gives off the right recurrent laryngeal nerve.

- Trace the right recurrent laryngeal nerve to the right lateral surface of the trachea and esophagus.

- The left vagus nerve passes on the left side of the aortic arch, where it gives off the left recurrent laryngeal nerve (we will see the origin of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve later). However, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve can be found on the left lateral surface of the trachea and esophagus at this time.

- Follow the right and left recurrent laryngeal nerves superiorly along the lateral surface of the trachea and esophagus. Trace them as far as the first tracheal ring. Do not follow them into the larynx at this time.

- Trace the phrenic nerve where it passes vertically down the anterior surface of the anterior scalene muscle (Fig. 7.13) posterior to the transverse cervical and suprascapular arteries.

- Use blunt dissection to define the borders of the anterior scalene and middle scalene muscles. The anterior and middle scalene muscles attach to the first rib. The first rib and the adjacent borders of the anterior and middle scalene muscles form the boundaries of the interscalene triangle. Observe that the subclavian artery and the roots of the brachial plexus pass between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, through the interscalene triangle (Fig. 7.13).

- Use blunt dissection to clean the roots of the supraclavicular part of the brachial plexus at the level of the interscalene triangle.

IN THE CLINIC:

The interscalene triangle becomes clinically significant when anatomical variations (additional muscular slips, an accessory cervical rib, or exostosis on the first rib) narrow the interval. As a result, the subclavian artery and/or roots of the brachial plexus may be compressed, resulting in ischemia and/or nerve dysfunction in the upper limb.

The interscalene triangle becomes clinically significant when anatomical variations (additional muscular slips, an accessory cervical rib, or exostosis on the first rib) narrow the interval. As a result, the subclavian artery and/or roots of the brachial plexus may be compressed, resulting in ischemia and/or nerve dysfunction in the upper limb.

Dissection Review

- Replace the infrahyoid muscles and sternocleidomastoid muscle in their correct anatomical positions. Review the boundaries of the posterior cervical triangle. Review the attachments of the infrahyoid muscles. Review the distribution of the cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus.

- Review the three parts and the branches of the subclavian artery.

- Review the distribution of the transverse cervical, suprascapular, and dorsal scapular arteries to the superficial muscles of the back and scapulohumeral muscles.

- Use an illustration to review the course of the vertebral artery from its origin on the first part of the subclavian artery to the cranial cavity.

- Review the relationship of the parathyroid glands to the thyroid gland. Use an embryology textbook to review the origin and migration of the thyroid and parathyroid glands during development.

- Review the relationship of the thyroid gland to the infrahyoid muscles, carotid sheaths, larynx, and trachea.

- Use an illustration and the dissected specimen to review the blood supply and venous drainage of the thyroid gland. Note that there are only two thyroid arteries (superior and inferior) but there are three thyroid veins (superior, middle, and inferior).

PAROTID REGION, TEMPORAL AND INFRATEMPORAL FOSSAE

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this laboratory assignment, the student will be able to:

Upon completion of this laboratory assignment, the student will be able to:

- Identify and describe the structures, including arteries and nerves, associated with the parotid region.

- Identify and describe the muscles of mastication.

- Identify the branches of the maxillary artery.

- Identify the nerves associated with the infratemporal fossa.

- List the nerve fibers that pass through or synapse in the otic ganglion.

- Describe the basic structures associated with the temporomandibular joint.

- Visualize and relate structures of the parotid region and infratemporal fossa with respect to adjacent structures.

The temporal fossa is located superior to the zygomatic arch and it contains the temporalis muscle. The infratemporal fossa is inferior to the zygomatic arch and deep to the ramus of the mandible. The infratemporal fossa contains the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V3), and the maxillary vessels and their branches. The infratemporal and temporal fossae are in open communication with each other through the opening between the zygomatic arch and the lateral surface of the skull.

The dissection will proceed as follows: The masseter muscle will be studied. The zygomatic arch will be detached and the masseter muscle will be reflected with the arch attached to it. The temporalis muscle will be studied. The coronoid process of the mandible will be detached and the temporalis muscle will be reflected with the coronoid process attached to it. The superior part of the ramus of the mandible will then be removed and the maxillary artery will be traced across the infratemporal fossa. The branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve will be dissected. The medial and lateral pterygoid muscles will be studied.

Osteology: Parotid Region, Temporal and Infratemporal Fossae

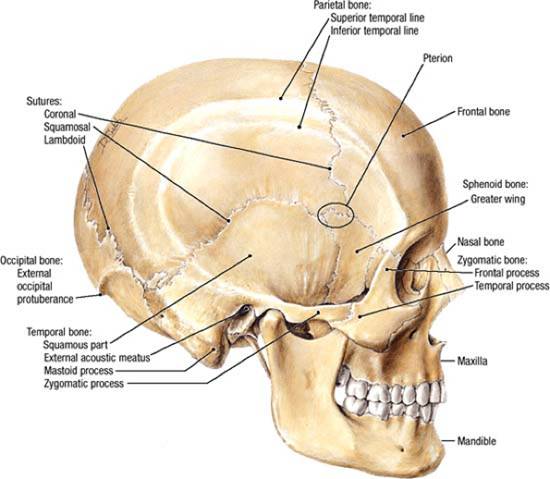

- On a skull, identify the boundaries of the temporal fossa:

- Deep - parts of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones

- Superficial - temporal fascia

- Superior and posterior - superior temporal line

- Anterior - frontal and zygomatic bones

- Inferior - zygomatic arch, infratemporal crest of the sphenoid bone, mandibular fossa, and articular tubercle. The zygomatic arch is formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone and the temporal process of the zygomatic bone.

- Review the location of the pterion

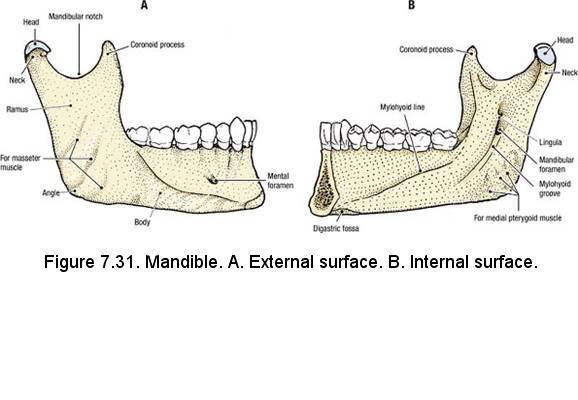

- From a lateral view of the mandible, identify (Fig. 7.31A):

- Head

- Neck

- Mandibular notch

- Coronoid process

- Ramus

- Angle

- On the internal surface of the mandible, identify (Fig. 7.31B):

- Lingula - for the attachment of the sphenomandibular ligament

- Mandibular foramen - for the inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein

- Mylohyoid groove - for the mylohyoid nerve and vessels

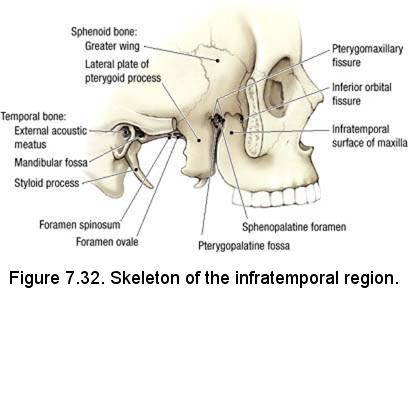

- Remove the mandible from the skull and view the bones of the infratemporal fossa from the lateral perspective. Identify (Fig. 7.32):

- Inferior orbital fissure - between the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and the maxilla

- Infratemporal surface of the maxilla

- Greater wing of the sphenoid bone - contains the foramen ovale and the foramen spinosum

- Lateral plate of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone

- Pterygomaxillary fissure - between the lateral plate of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone and the maxilla

- Reposition the mandible on the skull and identify the boundaries of the infratemporal fossa:

- Superior - the zygomatic arch (superficially) and the infratemporal crest of the sphenoid bone (deeply)

- Lateral - ramus of the mandible

- Anterior - the infratemporal surface of the maxilla

- Medial - lateral plate of the pterygoid process

- Roof - greater wing of the sphenoid bone

Dissection Instructions: Masseter Muscle and Removal of the Zygomatic Arch

- Cut and reflect the facial nerve branches and the parotid duct anteriorly.

- Clean the lateral surface of the masseter muscle. The superior attachment of the masseter muscle is the inferior border of the zygomatic arch and its inferior attachment is the lateral surface of the ramus of the mandible. The masseter muscle elevates the mandible (closes the jaw) and protrudes the mandible. It is innervated by the masseteric branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V3).

- Cut the temporal fascia along the superior temporal line and use a scalpel to peel it inferiorly. Observe that the temporalis muscle is attached to the deep surface of the temporal fascia. Cut the temporal fascia along the superior border of the zygomatic arch and remove the fascia completely.

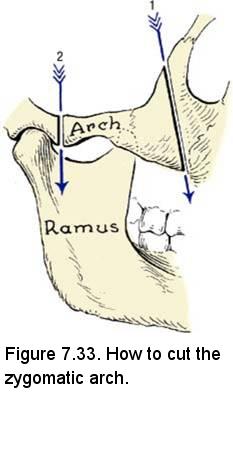

- Insert a probe deep to the zygomatic arch as close to the orbit as possible (Fig. 7.33, arrow 1). Use a saw to cut through the zygomatic bone to the probe.

- Insert the probe deep to the zygomatic arch near the anterior border of the head of the mandible (Fig. 7.33, arrow 2). Use a saw to cut through the zygomatic arch to the probe.

- Reflect the masseter muscle and the attached portion of the zygomatic arch in the inferior direction. Use a scalpel to detach the masseter muscle from the superior part of the ramus of the mandible, but leave the masseter muscle attached to the inferior part of the ramus, near the angle. During reflection, the masseteric nerve, artery, and vein will be cut.

Dissection Instructions: Temporal Region and Infratemporal Fossa

- Note that the temporal vessels and the auriculotemporal nerve are located in the scalp, superficial to the temporal fascia. The primary content of the temporal fossa is the temporalis muscle.

- Identify the temporalis (temporal) muscle. Observe:

- The temporalis muscle was attached to the deep surface of the temporal fascia.

- The inferior attachment of the temporalis muscle is the coronoid process of the mandible.

- Fibers of the anterior portion of the temporalis muscle have a vertical direction (elevation of the mandible).

- Fibers of the posterior portion of the temporalis muscle have a more horizontal direction (retrusion of the mandible).

- Wear eye protection for all steps that require the use of bone cutters.

- The ramus of the mandible must be removed to view the contents of the infratemporal fossa. The ramus of the mandible must be removed on both sides of the head to permit the head to be bisected in a later dissection step.

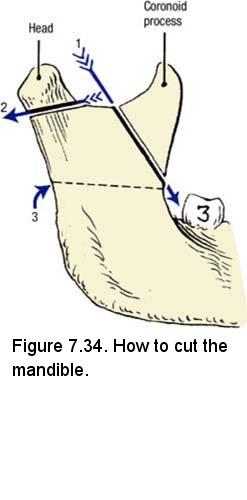

- The first step is to remove the coronoid process and reflect the temporalis muscle with the coronoid process attached. Insert a probe through the mandibular notch and push it anteroinferiorly toward the third mandibular molar tooth (Fig. 7.34, arrow 1). Keep the probe in close contact with the deep surface of the mandible. Use a saw to cut through the coronoid process to the probe.

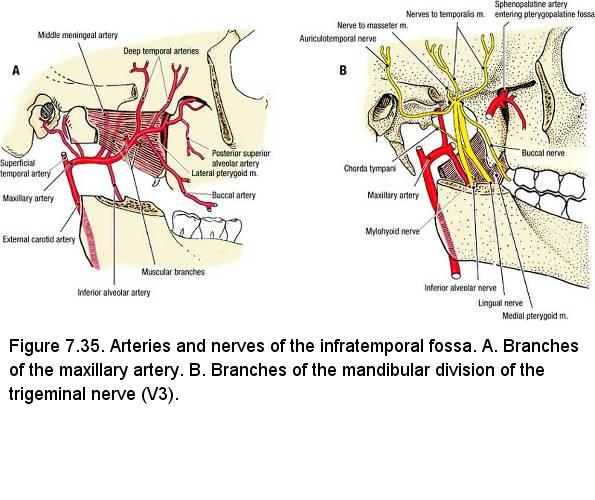

- Reflect the coronoid process together with the temporalis muscle in the superior direction. Use blunt dissection to reflect the temporalis muscle far enough superiorly to reveal the infratemporal crest of the sphenoid bone. Note that the deep temporal nerves (branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve) enter the muscle from its deep surface (Fig. 7.35B). The deep temporal nerves provide motor innervation to the temporalis muscle and they are accompanied by deep temporal arteries.

- Insert a probe medial to the neck of the mandible (Fig. 7.34, arrow 2). Use a saw to cut through the neck of the mandible.

- Cut along the upper 1/3 of the ramus of the mandible to avoid cutting the inferior alveolar vessels and the inferior alveolar nerve which go into the mandibular foramen. It is helpful to place a probe deep to the ramus and pull it hard up against the bone. Then slide the probe inferiorly until you encounter resistance as it is stopped by the lingula. Cut just above the probe to protect the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels.

- Remove the piece of the ramus of the mandible. You will come upon quite a bit of fascia, fat, and a venous plexus in this region. You need to carefully clean the dissection field.

- Identify the lateral pterygoid muscle (Fig. 7.35A). The lateral pterygoid muscle has two heads. The anterior attachment of the superior head is the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The anterior attachment of the inferior head is the lateral surface of the lateral plate of the pterygoid process. The posterior attachments of the lateral pterygoid muscle are the articular disc within the capsule of the temporomandibular joint and the neck of the mandible. The lateral pterygoid muscle depresses and protrudes the mandible (opens the jaw).

- Inferior to the lateral pterygoid muscle, identify the inferior alveolar nerve, artery, and vein (Fig. 7.35). Clean the inferior alveolar nerve and follow it to the mandibular foramen (Figure 7.31B). You may need to carefully remove more of the ramus of the mandible to gain more access the medial aspect of the mandible. Note that the mylohyoid nerve arises from the inferior alveolar nerve just before it enters the mandibular foramen and runs in the mylohyoid groove (Figure 7.31B).

- The inferior alveolar nerve and vessels enter the mandibular foramen and pass distally in the mandibular canal. Note that the inferior alveolar nerve provides sensory innervation to the mandibular teeth. The mental nerve is a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, which passes through the mental foramen to innervate the chin and lower lip.

- Identify the lingual nerve (Fig. 7.35B). The lingual nerve is located just anterior to the inferior alveolar nerve. The lingual nerve passes medial to the third mandibular molar tooth and it innervates the mucosa of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and floor of the oral cavity.

- Inferior to the lateral pterygoid muscle, identify the medial pterygoid muscle (Fig. 7.35B). The lingual nerve and inferior alveolar nerve pass between the inferior border of the lateral pterygoid muscle and the medial pterygoid muscle and can be used as guides to separate the two muscles. The proximal attachments of the medial pterygoid muscle are the maxilla and the medial surface of the lateral plate of the pterygoid process. The distal attachment of the medial pterygoid muscle is the inner surface of the ramus of the mandible. The medial pterygoid muscle elevates the mandible (closes the jaw) and protrudes it.

- Dissect the external carotid artery from the carotid triangle of the neck until it bifurcates into the maxillary and superficial temporal arteries (Fig. 7.35A). The maxillary artery crosses either the superficial surface (two-thirds) or the deep surface (one-third) of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

- [ON ONE SIDE ONLY] Remove the lateral pterygoid muscle to see the deeper part of the infratemporal fossa. Define the inferior border of the lateral pterygoid muscle by inserting a probe between it and the medial pterygoid muscle. Disarticulate the head of the mandible from the temporomandicular joint. Reflect the lateral pterygoid muscle medially and cut its attachment to the sphenoid bone. Be careful to preserve superficially positioned nerves and vessels.

- Use blunt dissection to trace the maxillary artery through the infratemporal fossa. The maxillary artery has 15 branches, of which we ask you to identify three. Identify only the arteries that are bolded in this and the next step (Fig. 7.35A):

- Middle meningeal artery - arises medial to the neck of the mandible and courses superiorly, passing through a split in the auriculotemporal nerve. The middle meningeal artery passes through the foramen spinosum, enters the middle cranial fossa, and supplies the dura mater. This relationship with the auriculotemporal nerve and the foramen spinosum will only be seen after the lateral pterygoid muscle is removed.

- Deep temporal arteries (anterior and posterior) - pass superiorly and laterally across the roof of the infratemporal fossa at bone level and enter the deep surface of the temporalis muscle.

- Masseteric artery (cut in a previous dissection step) - courses laterally and passes through the mandibular notch to enter the deep surface of the masseter muscle.

- Inferior alveolar artery - enters the mandibular foramen with the inferior alveolar nerve.

- Buccal artery - passes anteriorly to supply the cheek.

- Follow the maxillary artery toward the pterygomaxilliary fissure. Before disappearing into the pterygomaxilliary fissure, the maxillary artery divides into four branches: posterior superior alveolar artery, infraorbital artery, descending palatine artery, and sphenopalatine artery. At this time, you may be able to identify only the posterior superior alveolar artery, which enters the infratemporal surface of the maxilla (Fig. 7.35A). The other branches will be seen on a prosection later.

- Use a probe to follow the inferior alveolar nerve and the lingual nerve to the foramen ovale in the roof of the infratemporal fossa (Fig. 7.35B). Identify the chorda tympani, which joins the posterior side of the lingual nerve (Fig. 7.35B).

- Trace the middle meningeal artery through the split in the auriculotemporal nerve and into the foramen spinosum. The auriculotemporal nerve does not always split around the middle meningeal artery, but always passes nearby. Trace the auriculotemporal nerve laterally to the anterior side of the external acoustic meatus, just posterior to the ramus of the mandible.

IN THE CLINIC: Dental Anesthesia

A mandibular nerve block is produced by injecting an anesthetic agent into the infratemporal fossa. Understand from your dissection that the mandibular nerve block will anesthetize not only the mandibular teeth, but also the lower lip, the chin, and the tongue.

A mandibular nerve block is produced by injecting an anesthetic agent into the infratemporal fossa. Understand from your dissection that the mandibular nerve block will anesthetize not only the mandibular teeth, but also the lower lip, the chin, and the tongue.

Dissection Review

- Review the attachments and actions of the four muscles of mastication (masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid).

- Use an atlas illustration to study the origin of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V3) at the trigeminal ganglion and trace it to the foramen ovale. Follow the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve through the foramen ovale into the infratemporal fossa. Review the sensory and motor branches of the mandibular division.

- Follow the external carotid artery from its origin near the hyoid bone to the infratemporal fossa.

- Review the course of the superficial temporal artery and the maxillary artery. Follow the branches of the maxillary artery that were identified in dissection to their regions of supply.

- Note the relationship of the middle meningeal artery to the auriculotemporal nerve.

- Use an illustration and the dissected specimen to preview the terminal branches of the maxillary artery.